Travel back to 9000 BC in ancient Mexico, where early communities shaped daily life; from morning tasks to meals by the fire.

Just so we’re all on the same page. Please ensure you’ve made yourself acquainted with my disclaimer

Home Life

We’re in a interesting in-between moment: post–Ice Age climate stability, hunter-gatherer lifestyle still dominant, but with early plant domestication starting in pockets (squash, chili peppers, amaranth). The whole landscape is shifting, and so are people’s shelters, tools, and daily rhythms.

Houses & Dwellings

You wouldn’t see permanent “villages” yet, but semi-permanent seasonal camps were a thing. People moved with resources, maybe inland during certain harvest seasons, down to the coast for shellfish runs, or to river valleys when fish were plentiful.

Types of dwellings in 9000 BC Mexico:

- Brush huts: poles or branches set in a circle, bent inward to form a dome, covered with thatch, reeds, palm leaves, or grass mats. Common in lowland/coastal areas.

- Lean-tos: poles set at an angle against a frame, with hides or woven mats as covering. Used in drier areas or for temporary shelter.

- Rock shelters & caves: in mountainous or canyon areas, especially in the north and central highlands. These were prime real estate: stable temperature, protection from rain, sometimes with built-up walls of stone or earth at the entrance.

- Pit houses (emerging in some regions): shallow pits dug into the ground, roofed with poles, brush, and earth. Offered insulation from both heat and cold.

Sleep Schedules & Beds

- Sun-driven schedule: people slept soon after dark, woke with the dawn. Firelight extended evening activity but mostly for socializing, tool repair, or cooking.

- Segmented sleep: there’s evidence from many preindustrial societies that people had “first sleep” and “second sleep,” waking briefly in the middle of the night for quiet talk, tending the fire, or checking traps.

- Midday rest: in hotter climates, people likely took short breaks or naps in shaded spots, especially during the rainy season heat.

Beds

- No frames, bedding was on packed earth, rock shelves, or low woven mats made from reeds or palm leaves.

- Sleeping hides or mats to insulate from ground chill. In cooler highlands, animal skins or woven blankets from plant fibers added warmth.

- No pillows, maybe a folded hide or bundled cloth.

Major Tools/Things

Between 13,000 BC and 9000 BC, people in Mexico went through some big shifts:

“Mano and Metate.” Chaco Culture National Historical Park Museum Collection, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior

- Projectile Technology Upgrade

- In 13,000 BC hunting tools were large Clovis-style spear points for megafauna and by 9,000 BC it had moved to smaller, region-specific points for deer, turkey, and rabbits.

- The atlatl (spear-thrower) became more widespread, which gave more force and distance to throws.

- Food Processing Tools

- Shift from purely flaked stone blades to manos and metates (hand-held grinding stones and flat slabs, see image above) for seeds, amaranth, and chili peppers.

- More polished stone tools, longer-lasting, better edges.

- Fire pits with heated stones for slow cooking in earth ovens.

- Fishing Innovations

- Barbed bone and shell fishhooks

- Weighted nets or lines

- Rafts from reeds or logs for near-shore fishing

- Containers

- More woven baskets for carrying and storing seeds, tubers, fruits.

- Early gourd containers (bottle gourds were cultivated earlier for carrying water and food).

- Stone bowls and hollowed wood containers for mixing and holding cooked food.

- Shelter Enhancements

- Better thatching and mat weaving for rainproof huts in the tropics.

- Stone walling in caves and rock shelters for insulation and security.

Fashion & Beauty Standards

Alright, let’s time travel back to 9000 BC Mexico and talk style and yes, even here, style existed. Not “runway” style, but the deeply human, “this is how we show identity, attractiveness, and belonging” kind.

Clothing Materials & Construction

At this point, we’re pre-weaving textiles, so clothing is more about draped, wrapped, or tied materials rather than sewn garments:

Materials:

- Animal hides & furs: deer, rabbit, peccary, wild turkey feather capes in some areas.

- Plant fibers: agave, yucca, palm, and bark fibers softened and twisted into cords or mats.

- Woven mats: from reeds or grasses, used for capes, skirts, or weather shields.

- Feathers: decorative, sometimes layered onto capes or belts.

- Shells and beads: both as decoration and status markers.

Silhouettes:

- Wrap skirts or loin coverings for warm climates.

- Hide capes or poncho-like drapes in highlands or cooler nights.

- Simple cords or belts to secure wraps at the waist.

- Little distinction between “men’s” and “women’s” garment types, climate and activity dictated more than gender norms.

Fastenings:

- Thongs/cords of twisted plant fiber or rawhide.

- Knots and simple ties — no buttons, clasps, or pins yet.

Accessories & Adornment

Humans have always decorated themselves, and here’s what we likely see in Mexico 9000 BC:

- Shell beads (even inland, as small-scale exchange existed).

- Stone beads: especially jadeite in the south and other colorful stones in local zones.

- Bone ornaments: carved from hunted animals.

- Feather adornments: headbands, hair ties, or earrings.

- Piercings: ear piercings were possible with bone awls; nose piercings also plausible in some groups.

- Tattoos & body painting: plant dyes, charcoal, and ochre for both decoration and ritual markings.

Hair, Grooming, & Facial Hair

Facial and body hair were almost nonexistent for the people of this era and region. Genetically, early Mesoamerican populations, descendants of East Asian ancestors, had very sparse facial and body hair. Men did not grow full beards; at most, a few fine strands on the chin or upper lip. These were often plucked individually, both for tidiness and aesthetics. Tools like sharp stone flakes or bone tweezers may have been used for plucking, but shaving was unnecessary and virtually unknown.

Hairstyles

- Men: Likely wore medium to long hair, sometimes tied back with plant fibers or leather thongs for hunting or daily work. Short haircuts were rare because cutting tools were limited.

- Women: Probably had long, well-maintained hair, often braided or tied for practicality. Hair could be decorated with feathers, shells, or plant fibers.

- Haircare: No combs as we know, but they probably used their fingers for detangling. Plant oils, animal fats, or clay could have been applied to condition hair and protect against sun.

Natural Cleansers

People of this time were hunter-gatherers, relying on rivers, plants, and soil for hygiene. They didn’t have soap as we know it, but nature provided surprisingly effective alternatives.

Blooming Yuccas – Photo by Patrick Hendry on Unsplash

Yucca Root: Nature’s Soap

The yucca plant, common in ancient Mesoamerica, was an early source of natural cleansing power thanks to compounds called saponins.

Yucca’s saponins act the same way as soap today, reducing surface tension, surrounding grease and dirt, and allowing them to rinse away with water. This is an amazing case of convergent discovery: early humans intuitively found what chemists would explain millennia later!

How it was used:

- Roots were dug up and peeled to expose the saponin-rich flesh.

- People would pound or mash the roots in water until it foamed.

- This mixture was rubbed on skin and hair for washing, this was also used to clean hides and tools.

Other Natural Cleansers

- Water + Sand: River washing with coarse sand acted as a physical scrub.

- Wood Ash: Leftover from fires, ash is alkaline and acted as a primitive degreaser for hands after meat processing.

- Clay/Mud: Clay could absorb oils and dirt, working as an early “mask.”

- Fragrant Herbs: Sage-like plants and resinous herbs were crushed and rubbed on skin for odor control and mild antibacterial benefits.

- Smoke Cleansing: Burning aromatic plants (like copal resin or wild sage) not only served spiritual purposes but also helped fumigate skin and hair from pests.

Cosmetics & Body Decoration

- Pigments: red ochre, charcoal black, white clay, and plant dyes.

- Used for: face painting, body designs, symbolic markings in ceremonies.

- Patterns could mark group affiliation, achievements, or life events.

Body Ideals & Beauty Norms

Weight & Body Shape:

- Diet and activity meant most were lean and muscular by default. Fatness would be rare and might signal temporary abundance rather than a beauty ideal.

- Stamina, visible strength, and healthy skin were universal attractiveness markers.

- For people living in central and southern Mexico around 9000 BC, average adult stature was generally on the shorter side by modern standards, reflecting a forager lifestyle, variable nutrition, and some early experimentation with plant cultivation.

- Estimated Average Heights

- Men: ~5 ft 4 in to 5 ft 6 in (about 163–168 cm)

- Women: ~5 ft 0 in to 5 ft 2 in (about 152–158 cm)

- Estimated Average Heights

Differences in Male and Female Appearance:

- Clothing differences between genders were minimal, adornment choices (feathers, bead patterns, body paint motifs) carried more gendered signals than cut or fabric.

- Beauty norms were tied more to health, skill, and personal adornment than to strict differences between men and women..

Diet & Daily Meals

Explore what they grew, hunted, cooked, and craved.

Staple Foods

We’re right at the end of the Pleistocene and start of the Holocene, which means:

- Megafauna (mammoth, giant sloth) are gone or nearly gone, small and mid-sized animals are now the main protein.

- Domestication is just starting, we have very early squash, bottle gourds, chili peppers, and possibly amaranth cultivation in certain pockets.

- Still primarily hunter-gatherer diets, with seasonal shifts.

Animal Protein

- Small game: rabbit, peccary, armadillo, iguana, wild turkey, quail

- Insects: grasshoppers, ant larvae, beetles

- Fish & Shellfish: for coastal and river groups. Fish, crabs, clams, oysters, turtles

- Occasional big game: deer, tapir

Plant Foods

- Early domesticated squash (fleshy, small-fruited)

- Wild chili peppers (Capsicum annuum)

- Wild amaranth (seeds and leaves)

- Mesquite pods (sweet pulp)

- Prickly pear cactus (fruit and pads)

- Wild berries: elderberry, wolfberry, wild blackberries

- Wild fruits: guava relatives, sapote relatives (lowland tropics)

- Tubers: wild yams, jicama relatives, arrowroot-type plants

- Palm fruits (coastal lowlands)

Fats & Flavor

- Squash seeds (oil-rich)

- Avocado (in some tropical valleys — wild forms)

- Agave hearts (roasted in pits)

- Herbs: hoja santa, epazote, aromatic leaves

Sweeteners

- Wild honey (stingless bees)

- Sweet pulp of mesquite pods

- Naturally sweet fruits (prickly pear, guava)

Daily Time Spent Getting Food

9000 BC food systems were time-intensive but varied depending on location, season, and luck.

General pattern:

- Foraging/Gathering: 4–6 hours/day spread across morning and afternoon.

- Hunting/Fishing: Could be a quick 1–2 hour affair if lucky… or take the whole day.

- Food Processing/Cooking: 2–3 hours/day (grinding seeds, roasting, pit cooking).

- Farming: Minimal as early cultivation might take 1–2 hours/day for weeding, planting, or guarding small plots, but most food still came from wild sources.

- Trading: Small-scale and opportunistic, might take a few hours if traveling to a neighboring group’s seasonal camp, but wasn’t daily.

The 9000 BC Authentic Meal Plan

(As it would have been experienced in inland Mexico at this time)

What a Meal Really Looked Like in 9000 BC

- No formal plating or courses: food was eaten communally from shared cooked items.

- Portions were seasonal and opportunistic: the “main” was whatever protein or calorie-rich food was most available that day.

- Vegetables & starches weren’t “sides,” they were just cooked alongside the main food, often all in the same fire pit, hot stones, or leaf wrap.

- Dessert wasn’t separate: sweet foods were eaten when found, not held for the end of a meal. Prickly pear fruit might just be eaten as soon as it was picked.

- Beverages were simple: plain old H20

- Meals weren’t daily 3-square set times: people foraged and ate smaller things through the day, then had one larger cook-up when protein was available.

Morning:

- A handful of just-picked berries, elderberry and wolfberry

- A fist-sized piece of roasted squash saved from last night’s fire, eaten cool.

Midday Snack:

- Mesquite pods, chewed for their sweet pulp.

- A few grasshoppers roasted on a flat hot stone

- A small handful of toasted amaranth seeds if gathered in the morning.

Evening Cook-Up:

- A wild turkey dressed and rubbed with chili paste, wrapped in broad leaves along with chunks of early squash and starchy tubers.

- The bundle buried in a pit lined with heated stones, covered with earth, left to cook until the air smells of sweet squash and smoke.

- A piece of fresh honeycomb, straight from a wild hive.

Beverage:

- Water from a nearby spring

Modern-Twist Version

(Same flow, same seasonal spirit, but using common grocery store items and modern tools)

Morning:

- A small bowl of fresh blueberries and blackberries.

- Herbal tea made with hoja santa (or substitute with a mild anise-flavored tea like fennel) steeped in hot water from a kettle.

- Leftover roasted acorn squash wedge from last night, served at room temperature.

Midday Snack:

- Dried mesquite powder mixed into a spoonful of honey (instead of pods to chew).

- Toasted grasshoppers (chapulines, found in Mexican specialty stores) tossed in chili-lime seasoning.

- A tablespoon of popped amaranth seeds (lightly toasted in a dry skillet).

Evening Cook-Up:

- Bone-in turkey thighs rubbed with a paste of ground guajillo chili, garlic, and olive oil.

- Acorn squash chunks and cubed sweet potatoes wrapped in banana leaves (or foil) with the turkey, then roasted in the oven at 325°F for 2–3 hours.

- Honeycomb pieces atop garnished with a pinch of ground cacao nibs

Beverage:

- Still water with prickly pear purée stirred in and strained for a jewel-pink drink.

Climate & Environment

Alright, we’re talking Mexico, around 9000 BC, smack in the early Holocene. The Ice Age had ended a few millennia earlier, glaciers were gone, sea levels were still climbing, and climate patterns were stabilizing into something closer to what we recognize today, but with a few quirks.

We’ll split this into coastal lowlands, inland valleys, and highland plateaus, because a hunter-gatherer in the coastal tropics would’ve had a very different sweat factor than someone in the central highlands.

Coastal Lowlands (e.g., Gulf Coast, Pacific Coast)

- Average daily high: ~31–33 °C (88–91 °F)

- Average nightly low: ~23–25 °C (73–77 °F)

- Relative humidity: 70–85%

- How it felt: Heavy, even in shade, sweat beading before you finish your first berry-picking circuit. With humidity that high, skin never really dries, and breezes feel more like warm breath than cooling relief. Midday sun was oppressive; shade and water breaks were survival tactics.

Inland Valleys (e.g., present-day Oaxaca, Chiapas inland basins)

- Average daily high: ~26–28 °C (79–82 °F)

- Average nightly low: ~15–17 °C (59–63 °F)

- Relative humidity: 55–70%

- How it felt: Pleasant in the morning, cool enough for foraging treks without overheating. By midday, the sun would bite but the air was still breathable. Sweat evaporated more easily than on the coast, giving a lighter, drier warmth. Nights were cool enough to sleep comfortably with nothing more than a fiber mat.

Highland Plateaus (e.g., Central Mexican highlands)

- Average daily high: ~22–24 °C (72–75 °F)

- Average nightly low: ~10–12 °C (50–54 °F)

- Relative humidity: 45–60%

- How it felt: Brisk mornings, a strong warming once the sun hit, then crisp evenings. Sweat was minimal except during heavy labor in the sun. Nights could be chilly enough to huddle close to a fire or share body heat. The thin air and strong UV meant you felt the sun more than the thermometer suggested.

Population & Top Cities

Where were people living—and how many were there?

Estimated Population

- Range: ~50,000–150,000 people across all of what is now Mexico

- This is based on carrying capacity estimates for a hunter–gatherer landscape and archaeological finds from both coastal and inland regions.

- Population density: ~0.03 to 0.1 people per km² (incredibly sparse by modern standards).

Top 5 Largest Population Clusters

These are based on archaeological evidence of frequent occupation, tool-making debris, hearths, and food remains. Keep in mind these were seasonal or semi-permanent hubs.

- Valle del Tehuacán (Puebla)

- Importance: Rich in wild plant diversity, including early domesticated squash; nearby water sources.

- Why people gathered here: Year-round foraging and hunting in a mild climate; early seed-planting experiments.

- Population estimate in peak season: 200–400 people across multiple camps.

- Coastal Veracruz & Tabasco Wetlands

- Importance: Abundant fish, shellfish, and waterfowl; mangrove resources.

- Why people gathered here: Coastal trade in shells and dried fish with inland groups.

- Population estimate in peak season: 300–500 people spread along shore camps.

- Baja California Sur (Cape Region)

- Importance: Rich marine life, sea mammals, and year-round fishing.

- Why people gathered here: Stable food sources even in dry seasons inland.

- Population estimate in peak season: 150–300 people.

- Central Plateau Lakes Region (Valley of Mexico)

- Importance: Lakes like Texcoco and Xaltocan provided water birds, fish, edible plants.

- Why people gathered here: Seasonal gathering spot with fertile soils for early cultivation experiments.

- Population estimate in peak season: 200–400 people.

- Sierra Madre Occidental Foothills

- Importance: Game-rich woodlands, diverse plant life, and trade routes to both coast and desert.

- Why people gathered here: Strategic location for moving goods between ecological zones.

- Population estimate in peak season: 100–250 people.

Health

Alright, let’s put ourselves in 9000 BC Mexico, long before maize fields or pyramid cities, when your “healthcare plan” was basically: stay alive, avoid jaguars, and don’t fall.

Life Expectancy & Survival

- If you survived childhood:

- You could reasonably expect to live into your late 30s or early 40s, sometimes longer if you were very lucky and avoided major injury.

- Elders in their 50s existed, but they were rare and often revered for their knowledge.

- Child survival rate:

- Roughly 40–50% of children died before age 15.

- Infant mortality was especially high, about 20–25% didn’t survive their first year.

- This makes adulthood in ancient Mexico something of a statistical victory lap.

Healthcare & Medicine

No pharmacies, no stethoscopes, healing was handled through:

- Healers: While there is no record of healers, we can infer that people took notice of certain plants interacted with people’s bodies, and this was pasted down, and there are always those who just rock at comforting and healing.

- Herbal remedies:

- Prickly pear cactus for burns/wounds.

- Wild chili as an antimicrobial wash.

- Willow bark (a natural aspirin) for pain/fever.

- Mesquite gum for sore throats.

- Animal products: Fat for salves, bone splints for fractures.

- Herbal remedies:

- Childbirth: Birth assistance was almost certainly present, but provided through kin-based networks, especially experienced older women (mothers, grandmothers, aunts)

Common Health Issues/Causes of Death

- Infections: Cuts or tooth abscesses could be fatal without antibiotics.

- Parasites: Intestinal worms were common from untreated water and raw food.

- Severe Diarrhea: from contaminated water

- Malnutrition: Seasonal shortages sometimes led to lean months.

- Injuries: Hunting accidents, falls, and animal attacks.

- Joint & bone wear: From constant walking, carrying loads, and grinding seeds on metates.

- Childbirth complications: A major cause of death for women.

Hygiene Norms

- Bathing:

- Rivers, lakes, and streams were the primary bath spots.

- Full immersion likely happened weekly or during water gathering; quick rinses could happen daily if near water.

- Ash and sand might be used as mild abrasives to scrub skin.

- Dental care:

- No toothbrushes; likely used chewing sticks or fibrous plant stems.

- Tooth wear from grit in stone-ground food was severe.

- Menstrual care:

- Likely used soft plant fibers, moss, or folded animal skins; may have simply free-bled in secluded spots.

- Waste disposal:

- Latrines were not permanent; waste was buried away from camp.

- Camps were moved periodically, partly to avoid sanitation issues.

Social & Family Structure

Alright, let’s step into 9000 BC Mexico, when social life was small-scale but deeply interconnected, and your “neighborhood” was basically the people who shared your campfire.

Family & Household Structure

- Family units:

- Extended families were the norm, multiple generations and sometimes unrelated individuals banded together for survival.

- Groups were often bands of 20–50 people, made up of related families and a few outsiders who had joined by marriage or alliance.

- Living arrangements:

- Housing was communal in the sense that shelters were built close together, often in a circle or cluster, with shared fire areas.

- Childcare, food preparation, and tool-making were communal responsibilities.

Marriage Customs

- Monogamy was common, but not rigid.

- Average age at first marriage:

- Women: 14–17 (often soon after physical maturity).

- Men: 16–20, depending on proven hunting or tool-making skills.

Roles/Status

- Gender roles:

- Fairly defined by biology but flexible when needed.

- Men: Primarily hunted large game, did long-distance foraging, made heavier tools.

- Women: Foraged, trapped small animals, processed food, made clothing, cared for children.

- Both could gather plants, fish, and participate in community decisions.

- Elder respect:

- Elders were repositories of knowledge, migration routes, plant uses, seasonal timing, and highly respected.

- Their advice could override younger leaders in decisions affecting survival.

- Children’s roles:

- Learned skills early by imitation.

- By age 7–10, children could meaningfully contribute: carrying wood, helping with food prep, guarding supplies.

Childhood & Parenthood

What was it like to be a kid… or raise one?

Challenges of Childhood

- High mortality rate: Likely 50–60% of children didn’t reach adulthood, mostly from disease, malnutrition, or accidents. Surviving to 15 was like unlocking “hard mode complete” in life.

- Injury risk: No helmets, no childproofing, and plenty of open fire pits, stone tools, and wild animals.

- Nutritional swings: Diet could be feast-or-famine, especially in dry seasons.

- Exposure to the elements: Shelter was simple, so cold nights, hot days, and rain could be constant stressors.

- Predators & pests: Jaguars, snakes, large birds of prey, and insects carrying disease were all hazards.

Challenges of Parenthood

- Keeping children alive – Every day meant guarding them from injury, predators, and dangerous plants.

- Feeding the whole family – Food had to be hunted, gathered, or traded daily; no pantry safety net.

- Balancing labor – Parents couldn’t stop hunting, farming, or crafting just because a baby needed care; childcare and work happened simultaneously.

- Illness & injury without medicine – Parents had to treat sickness with herbs, heat, and prayer, knowing outcomes were uncertain.

- Emotional strain – High child mortality meant parents often lost children; grief was a regular part of life.

- Seasonal danger – Harsh dry or wet seasons could mean food scarcity, long migrations, or exposure to storms.

- Community pressure – Parents were judged on how skilled and obedient their children were; failing to raise competent kids could lower family standing.

Improvements

Here’s how life improved for children and parents in Mexico between 13,000 BC and 9,000 BC:

- Food Security Increased

- Then (13,000 BC): Families were fully dependent on hunting and gathering large, unpredictable animals like mammoths and mastodons. If a hunt failed, starvation risk was high.

- Now (9,000 BC): People started early plant domestication (squash, beans, chili peppers). This provided more consistent food for kids and reduced famine risk. Parents could plan better.

- Safer Settlements

- Then: Constant movement following herds = dangerous terrain, exposure to predators, and unstable shelter.

- Now: Semi-permanent camps near rivers and fertile valleys allowed more stable homes, making life easier for small children (less carrying, more play).

- Reduced Hunting Hazards

- Then: Hunting giant megafauna (mammoth, giant sloth) was extremely dangerous. Many hunters died, leaving families vulnerable.

- Now: Focus on smaller game (turkey, deer, rabbits) and fishing meant less life-threatening risk for parents, creating stronger family stability.

- More Reliable Infant Nutrition

- Then: Nursing mothers struggled if food was scarce; toddlers often went hungry during lean months.

- Now: Early use of wild beans, squash, seeds, and nuts as supplemental foods for toddlers provided better calorie security beyond breast milk.

- Improved Community Support

- Then: Small bands with limited members, so if a parent died, survival odds for kids dropped drastically.

- Now: Larger social groups and shared childcare in camps meant orphans and widowed parents had community support.

Parenting Norms

- Mothers: Primary caregivers in infancy, responsible for feeding, carrying, and teaching survival skills like gathering safe plants.

- Fathers: Often hunters or toolmakers, but also teachers for older children (especially boys) in tracking, fishing, and defense.

- Grandparents: Knowledge keepers. They told origin stories, trained children in traditions, and helped with light childcare.

- Discipline: Direct and practical: if a behavior endangered the group or food supply, correction was immediate and public. Shaming could be used, but physical punishment was rarer than simply giving more responsibility as a “lesson.”

- Affection levels: Surprisingly high. Babies were carried constantly in woven slings, and young children lived in close contact with the entire community. Physical closeness was the norm.

Pets & Animal Companions

- Early dogs: Domesticated for hunting help, guarding, and warmth at night. They weren’t “pets” in the modern sense, but they did bond with families.

- Turkeys: Semi-domesticated for feathers and eventual food (though more common later in history).

- Small parrots & macaws: In more tropical zones, sometimes kept for feathers and companionship.

Leisure & Recreation

How did people have fun?

Adults

Popular Pastimes: In 9000 BC Mexico, there were no taverns or theaters, but adults certainly had ways of creating meaning and connection beyond daily survival. Social storytelling was central: oral traditions served as both entertainment and a cultural archive. Dance and rhythmic movement likely played a role in ritual gatherings, reinforcing group identity and any spiritual beliefs.

Leisure & Communal Activities: “Time off” was often integrated with subsistence. Foraging trips, tool-making, and food preparation doubled as opportunities for socialization. Communal feasting after successful hunts or harvests would have been significant cultural events, combining practical necessity with celebration.

Holidays & Events: While formal holidays didn’t exist, seasonal markers such as the onset of rains or the ripening of key food sources may have prompted collective gatherings. These were deeply tied to survival cycles and spiritual interpretations of nature.

Children & Families

Games and Play: Children’s play was both recreation and training for adult life. Imitative games, mimicking hunting or food gathering, were common. Simple physical contests like chasing games (precursors to tag) likely occurred, fostering agility and endurance. Objects from nature, sticks, stones, gourds, could serve as toys or props for imaginative play.

Family Dynamics: Play also happened in the presence of adults during communal tasks, with learning embedded in observation and participation. There were no formal “childhood” phases as we define them; play was preparation for contribution.

Cultural Gatherings for Children: For younger members, communal storytelling around the fire was a primary source of entertainment and cultural education. These narratives transmitted survival knowledge and social norms, while also providing a sense of belonging.

Culture, Language & Religion

Explore the worldview, values, and art of the time.

Religious & Spiritual Life

- Nature-Based Spirituality: Organized religion as we know it didn’t exist yet, but spirituality was deeply embedded in daily life. People likely attributed life cycles, fertility, death, and natural phenomena (rain, drought, animal migrations) to unseen forces or spirits.

- Gods & Beings: There is no evidence of named deities this early in Mesoamerica; those emerge thousands of years later. However, the animistic worldview, believing everything (plants, rivers, animals) had a spirit, was likely present.

- Rituals & Practices:

- Burial customs: Archaeological sites from this era show intentional burials, sometimes with red ochre, suggesting belief in an afterlife.

- Offerings: Simple food offerings or symbolic items may have been placed with the dead.

- Moral Code: Likely centered on communal survival, cooperation, reciprocity, and maintaining harmony with nature. Violating taboos around food-sharing or hunting practices would have been serious social infractions.

Art & Aesthetics

- Defining Style: Early art was practical and symbolic, not decorative in the later sense.

- Media:

- Rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs): Abstract shapes, animal depictions, hunting scenes.

- Carvings in bone or antler: Used for tools and symbolic markings.

- Beadwork & body decoration: Shells, seeds, pigments for personal adornment.

- Purpose: Art was inseparable from function. Tools, clothing, and ritual objects often had symbolic markings.

Language & Communication

- Dialect Diversity: Likely multiple proto-languages ancestral to later Oto-Manguean, Mayan, and Uto-Aztecan families.

- Script: None at this stage, iconography and symbolic markings were not formal writing but could convey meaning (territorial or ritual markers).

What’s Been Happenin’?

Significant Advancements Since 13,000 BC. From 13,000 BC to 9,000 BC, societies in the region that would become Mexico transitioned dramatically:

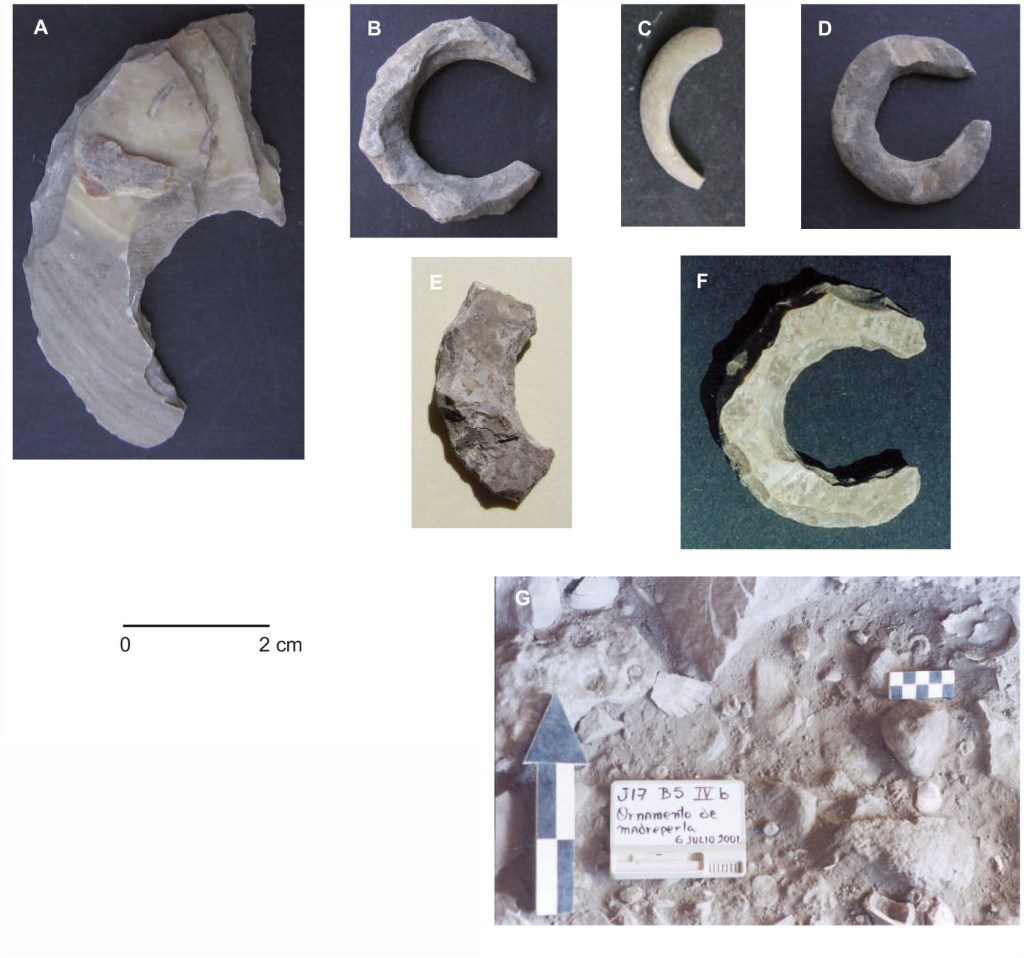

Circular shell artifacts, probably fishhooks, crafted from pearl oyster shells. These come from an Early Holocene coastal location on Espíritu Santo Island, Baja California Sur. They show just how early humans in the region were innovating with marine resources for survival.

1. From Big Game Hunting to Broad-Spectrum Foraging

- Clovis culture decline (≈11,000 BC): The era of hunting megafauna (mammoths, mastodons) waned as these animals became extinct, likely due to a combination of overhunting and climate change.

- Diet Diversification: People shifted toward smaller game (deer, rabbits, birds) and a wider array of wild plants, roots, nuts, and seeds. This was a huge cultural pivot—think of it as moving from a “single food subscription” to an “all-you-can-eat local buffet.”

2. Early Plant Domestication (Proto-Agriculture)

- Around 10,000–9,000 BC, evidence emerges of incipient plant cultivation, especially:

- Squash (Cucurbita pepo): One of the earliest domesticated plants in the Americas, grown for seeds and gourds (storage containers, utensils).

- Teosinte experimentation: This wild grass was a distant ancestor of maize (corn). People began selective gathering, setting the stage for full domestication millennia later.

- Why is this big? It marks the start of human-directed ecosystems, leading eventually to farming villages.

3. Technological Innovations

- Stone Tools: Projectile points became smaller and more efficient for hunting smaller prey.

- Grinding Stones (Manos and Metates): Used for processing seeds, roots, and possibly early cultivated plants, a key step toward a plant-based diet.

- Fire Management: Controlled burning of landscapes for resource renewal became a practiced technique.

4. Climate Instability

- At the tail end of the Ice Age, the world was warming, then suddenly slammed into the Younger Dryas (≈10,900–9,700 BC), a thousand-year cold snap that hit the brakes on progress. Foragers in what is now Mexico faced leaner resources and had to hustle harder for calories.

- By around 9,700 BC, the chill lifted for good. The Holocene kicked in, bringing a relatively stable, warmer climate. Grasslands gave way to forests, rivers swelled, and plants like squash and gourds thrived. This shift set the stage for the first steps toward domestication, and the slow pivot from pure hunting to mixed strategies.

- People responded by broadening diets, becoming highly mobile, and establishing seasonal camps.

2. Megafaunal Extinction

- By 9000 BC, iconic animals like mammoths, mastodons, and giant ground sloths were gone.

- Impact: Loss of primary protein source → need for innovation (smaller game hunting, plant gathering).

3. Social and Cultural Change

- From large hunting bands to smaller, more flexible groups: Mobility remained key, but seasonal aggregation for resource-rich areas occurred (e.g., near rivers or lake margins).

- Art and Symbolism: While large cave murals (like in later Archaic periods) weren’t yet prevalent in Mexico, portable art (engraved stones, decorated bones) suggests early symbolic thinking persisted.

Music & Instruments

What did it sound like?

At this point, music was prehistoric, meaning no formal written compositions or recorded artists (sorry, no Mayan Spotify yet). However, sound-making was central to ritual and community life. The instruments were primitive but powerful, mostly made from natural materials.

Likely Instruments & Uses

- Bone Flutes – Made from bird bones; used for ritual ceremonies or signaling during hunts.

- Shell Trumpets (Conch) – Blown during spiritual gatherings or to call the community.

- Percussion Stones (Lithophones) – Stones struck together for rhythm in dances or ceremonies.

- Gourd Rattles – Dried gourds filled with seeds

- Drums (Early Huehuetl style) – Hollowed logs with stretched animal hide, providing deep rhythm for communal dances.

Media You Can Watch or Read Today

Here are some films, shows, or books that engage with prehistoric or early Indigenous eras, aiming to represent, or at least evoke, the world of early Mesoamerica in a compelling way. While none perfectly depict 9000 BC Mexico (due to the extreme scarcity of sources), each offers thematic or stylistic resonance. I’ve included a mix of Spanish and English works, noting dubbed or subtitled options where applicable.

Adults

1. 10,000 BC (Film, 2008)

- Language: English (original)

- Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish subtitles widely available

- Ages: Adult (PG-13, adventure)

- Description: It’s basically an epic adventure about mammoth hunters, but fair warning, it’s more Hollywood than history. Think pyramids, mammoths, and a whole lot of drama all mashed together. Fun to watch if you’re into big survival stories, just don’t go in expecting accuracy.

2. Quest for Fire (Film, 1981)

- Language: Constructed prehistoric language (no modern dialogue)

- Dubbed/Subtitled: Subtitles in English and other languages available

- Ages: Adult (PG)

- Description: This one’s about a tribe trying to get fire back, and honestly, it feels way more authentic than most movies in this genre. They even invented a language for it, which is pretty cool. Just a heads-up though, it’s set in the Old World, not the Americas, so not exactly Mexican prehistory, but still a fascinating watch.

3. Alpha (Film, 2018)

- Language: Fictional prehistoric language, minimal dialogue

- Dubbed/Subtitled: Subtitles in multiple languages, including Spanish

- Ages: Teen/Adult (PG-13, family-friendly survival story)

- Description: It’s a survival story about a young hunter who gets separated from his tribe and ends up bonding with a wolf. The whole “first human-dog friendship” angle is heartwarming. Just keep in mind, it’s set way earlier and in a totally different part of the world, so it’s not accurate for 9000 BC Mexico, but still a cool what-if story.

4. The Clan of the Cave Bear (Movie & Book)

- Language (Film): English

- Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish subtitles available

- Language (Book): English (original)

- Ages: Adult

- Description: It’s a novel (and later a film) about a Cro-Magnon girl raised by Neanderthals. Totally set in Europe, not Mexico, but if you’re into stories about survival, early humans, and cultural clashes, it’s a fascinating read, just don’t expect it to reflect what life looked like here in 9000 BC.

5. La edad de piedra (1964, Film)

- Language: Spanish (original)

- Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish only; English subtitles unlikely

- Ages: Family/Adult (comedic fantasy)

- Description: It’s a goofy time-travel comedy where people end up in “prehistoric Mexico.” Honestly, it’s not accurate at all, more cartoon cavemen than real history, but it’s fun if you’re in the mood for something silly with a prehistoric twist.

Kids

1. Las Leyendas (Netflix)

Language: Spanish (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 8–12

An animated series inspired by Mexican folklore and Indigenous mythological creatures. While not strictly historical, it introduces children to ancient cultural elements in a fun, spooky, and adventurous way.

2. Onyx Equinox (Crunchyroll)

Language: English (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish available

Ages: 13+ (older kids/teens)

An animated series deeply rooted in Aztec and Mayan mythology. It follows a young boy chosen by the gods to close the gates to the underworld. Darker themes but historically inspired with authentic cultural references.

3. The Legend of the Sun and the Moon (Book)

Language: English (available in bilingual editions)

Dubbed/Subtitled: N/A

Ages: 6–10

A retelling of an Aztec creation myth, explaining how the sun and moon came to be.

4. Feathered Serpent and the Five Suns: A Mesoamerican Creation Myth (Book)

Language: English

Dubbed/Subtitled: N/A

Ages: 6–10

A book of the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl and the myths of how the world was created.

Would you thrive in this time period, or struggle without plumbing and podcasts? Leave your thoughts below or tag me on social!

Leave a comment