Step into a world shaped by sun, maize, and ritual. In this post, we explore what daily life looked like in Mexico around 1100 AD, from how families woke with the light, to the foods simmering over clay hearths, to the beliefs that guided work, rest, and celebration.

Just so we’re all on the same page. Please ensure you’ve made yourself acquainted with my disclaimer

Home Life

Step into their house: how big was it, what did it look like, and how did people sleep or stay clean?

The Shape of a Home

Most houses were single-story, built from adobe, stone, or packed earth, with thick walls that stayed cool during the day and held warmth once the sun dropped. A typical home measured about 20–40 m² (215–430 sq ft), though size varied by region, climate, and family status.

Instead of “bedrooms” or “bathrooms,” homes were multi-use spaces:

- One main room for sleeping, eating, weaving, and storytelling

- The floor was packed earth that was swept and re-smoothed daily

- A hearth (usually a three-stone fire) near the center or wall

- An open patio or courtyard shared with extended family

- No fixed bathroom: cleanliness was handled differently (we’ll get there)

Beds, Sleep, and the Rhythm of Night

People slept close to the ground, on petates, woven mats made from palm fibers or reeds. They’re firm, breathable, and easy to roll up during the day. Add a cotton blanket (if you had one) or a maguey-fiber cloth and you’re all set.

Sleep followed the sun:

- Wake around sunrise

- Sleep shortly after sunset

And yes, naps were a thing. Especially after the midday meal, when the sun hit around 30–32 °C (86–90 °F) in much of central Mexico during the dry season. Short rests weren’t laziness; they were survival.

Cleanliness Without Bathrooms

People bathed in:

- Rivers, lakes, or canals

- Steam baths (temazcales): low stone structures heated with volcanic rock. A temazcal wasn’t just about hygiene. It was about:

- Healing muscles after labor

- Cleansing the body after childbirth or illness

- Spiritual renewal, where sweat marked transformation and release

Objects That Made a House a Home

A simple everyday container from ancient Mesoamerica that once sat in a home courtyard, holding water or food and bearing witness to breakfasts, chores, and conversations much like our own kitchens do today.

Homes didn’t have “furniture” like we think of it, but they were full of meaningful objects, tools that shaped daily life.

Inside, you’d almost always find:

- Metates and manos (stone grinding tools), smooth from generations of maize

- Clay ollas for storing water, beans, or cacao

- Woven baskets hanging from beams

- Textiles folded carefully, often dyed with cochineal or indigo

- Small household altars: simple, but deeply personal

Fashion & Beauty Standards

What did people wear and what did society expect them to look like?

First thing: styles vary by region, but the logic of dress is super consistent: clothing is climate + labor + identity, and then status gets layered on top like salsa on everything.

The Everyday Silhouette

Most outfits were simple shapes, rectangles and wraps, because woven cloth comes off the loom as, well… cloth. The genius is in how you fold it, tie it, and decorate it.

Common silhouettes you’d recognize across central Mexico:

- Men: maxtlatl (loincloth wrap) + tilmatli/tilma (rectangular cloak)

- Women: huipil (tunic) + cueitl (wrap skirt) + sometimes quechquemitl (triangular shoulder garment for higher-status / ceremonial moments, kinda poncho-ish)

Materials & Texture

- Maguey (agave) fiber: rougher, durable, everyday, think “workwear.”

- Cotton: softer, smoother, cooler, more accessible in some regions, but often tied to higher status in central Mexico.

- Feathers, fine embroidery, vivid dyes: not daily for most people, more special occasion.

Fastenings & Accessories

No zippers, no buttons, no problem. Everything is tied, wrapped, knotted, belted. You’d see sashes, simple ties, and clever draping.

Crafted by Mixtec (Ñuu Savi) artisans in Oaxaca between 1325–1521 AD

Jaguars have the strongest bite relative to their size of any big cat, delivering force up to seven times their body weight, strong enough to crush a skull and kill instantly. Wearing a jaguar pelt was an earned privilege, and referencing that power through gold jaguar-tooth beads, paired with the soft rattle of clapper-less bells as the wearer moved, clearly marked the status and authority of the person allowed to wear it.

Accessories weren’t just “cute.” They were status + protection + meaning:

- Ear ornaments (obsidian, shell, jade)

- Neck pieces / pectorals (stone, shell, sometimes jade in elite contexts)

- Hair bindings and bands that signaled age or rank

Footwear

Shoes were real, but minimal.

- Cactli (sandals) were common for both men and women

- Made from:

- leather

- fiber

- woven plant material

- Secured with straps tied around the ankle or foot

- Worn outdoors; often removed indoors or during certain rituals

- Made from:

Going barefoot also wasn’t shameful, it was situational. Shoes were for out and about and bare feet at home.

Body Modification

- Head binding (cranial modification): begun in infancy, using gentle pressure with boards or bindings to create elongated or flattened head shapes

- Ear piercing (especially for males entering adulthood or status roles)

- Body paint for ritual, warfare, or ceremony. Pigments for beauty + ritual: charcoal, minerals, plant dyes. Body paint is much easier to document than permanent tattoos here, so I’d describe it as paint + adornment more than “everyone had tattoos,” because the evidence is uneven by region and period.

- Occasional scarification or permanent marking, unevenly documented and likely region-specific

Average Height

Based on skeletal remains from central Mexico and surrounding regions (Valley of Mexico, Mixteca, Puebla-Tlaxcala area), anthropologists estimate:

- Adult men: ~160–165 cm (about 5 ft 3 in – 5 ft 5 in)

- Adult women: ~148–153 cm (about 4 ft 10 in – 5 ft 0 in)

These are averages, not limits. There were absolutely taller and shorter people, just like now. Some elite males likely pushed closer to 168–170 cm (5 ft 6–7 in), while populations under stress could average lower.

Diet & Daily Meals

Explore what they grew, hunted, cooked, and craved.

How They Thought About Food

People didn’t eat alone, distracted, or on the move. Meals were tied to home, community, and obligation, because feeding others was part of being a good person. Certain foods carried moral weight, especially maize, which wasn’t just a crop, but sacred.Maize was tied to creation stories and human identity itself. Wasting it, mistreating it, or eating without regard for social norms wasn’t just rude — it was morally wrong. Excess, greed, or eating at the wrong time or in the wrong way was criticized, not admired.

Staple Foods: The Daily Backbone

Zoom in on everyday life and the diet looks simple at first: few ingredients, endless technique. The same foods appear again and again across Mesoamerica, prepared differently depending on region, season, and household.

The core staples were:

- Maize: tortillas, tamales, atole, pozole-style preparations

- Beans

- Squash

- Chile

Bonus staples, depending on region and ecology, included amaranth, chia, avocado, sweet potato, and zapotes.

Because 1100 AD Mexico was regionally diverse, protein followed the landscape: fish near lakes and rivers, insects and small game in many areas, turkey in some regions, and more hunting where ecology allowed. The diet, in many ways, was a map.

Staple Drinks

Water, obviously. But daily life also had drinks that are basically portable meals.

Common drinks included:

- Atole: a maize-based drink or gruel, sometimes plain, sometimes flavored

- Cacao drinks: consumed in specific ritual, elite, or trade-related contexts, not as an everyday beverage

Mesoamerica had multiple fermentation traditions, just not that one as the default.

By or before 1100 AD, people were making:

- Pulque: fermented maguey sap, carefully regulated and ritualized

- Tesgüino / batári (northern regions): made from sprouted or malted maize

- Balché (in Maya regions): honey, tree bark, and water

Alcohol existed, but it was controlled, contextual, and often ceremonial rather than casual.

What Did a Normal Day of Eating Look Like?

Eating Style

- Communal bowls

- Food eaten by hand

- Tortillas used as utensils

Meals followed a rhythm tied to labor, daylight, and energy needs:

| Time of Day | Function | Food Reality |

| Early Morning | Fuel | Atole, leftover tortillas |

| Midday | Main intake | Tortillas, beans, squash, chile, occasional protein |

| Afternoon | Sustenance | Tortillas, fruit, seeds |

| Evening | Light meal | Leftovers, atole |

| Night | Rare | Ritual foods only |

How Much of Life Was Spent Getting Food?

A lot. Like… the day is built around food work, not the other way around.

Food time breaks down into a few big worlds:

- Farming (milpa work): seasonal heavy labor (planting, weeding, harvesting), plus constant upkeep

- Processing maize: nixtamalizing, grinding on a metate, shaping, cooking… this is daily and it’s a full time responsibility

- Trading/markets: many households relied on exchange networks rather than producing everything themselves

- Foraging/hunting/fishing: depends hard on region, season, and household role; it’s part of the food strategy

Food didn’t just appear. It was made… Every. Single. Day.

HISTORICAL PLAN

- Morning

- Snack

- Cold tortilla

- Plain jícama

- Main Meal

- Freshly made maize tortillas

- Boiled beans

- Chile sauce

- Roasted Sweet Potatoes

- Drink:

- Water or thin maize drink

- Treat (Natural richness instead of dessert)

- Avocado – Halved, eaten plain or with a pinch of salt or Chile

MODERN PLAN

Same structure · Same food logic · Modern execution

- Breakfast

- Silky Masa Atole Latte

- Snack

- Blue corn tortilla chips

- Chilled jícama sticks with lime and a pinch of flaky salt

- Dinner

- Sweet potato tacos — grilled sweet potatoes in fresh corn tortillas, topped with chile salsa

- Side of mashed beans

- Drink:

- Agua de maíz

- Dessert

- Chilled avocado crema – blended avocado with lime and agave

Climate & Environment

How did geography and weather shape daily life?

1. Northern Aridoamérica

(Desert & semi-desert zones — today parts of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Zacatecas)

Photo by Andrés Sanz on Unsplash

Climate

- Summer: ~35–40 °C (95–104 °F)

- Winter: ~5–15 °C (41–59 °F)

- Humidity: ~15–30%, feels dry-dry, cracked lips, fast evaporation

Landscape

- Desert scrub, rocky plains, thorny bushes, agave, nopales

- Few rivers, long distances between water sources

2. Valley of Mexico (Central Highlands)

(Mexico-Tenochtitlan region)

Climate

- Summer (rainy): ~22–26 °C (72–79 °F)

- Winter (dry): ~5–20 °C (41–68 °F)

- Humidity: ~40–60%, feels mild, breathable, occasionally cool

Landscape

- High-altitude basin (~2,200 m / 7,200 ft)

- Lakes, wetlands, volcanic soil, surrounding mountains

3. Oaxaca Valley

(Southern highlands, Mixtec & Zapotec regions)

Climate

- Summer: ~25–30 °C (77–86 °F)

- Winter: ~10–22 °C (50–72 °F)

- Humidity: ~40–55%, warm but not sticky

Landscape

- Rolling valleys, dry hills, forested ridges

- Terraced fields, seasonal rivers

4. Gulf Coast (Veracruz & Huasteca regions)

(Lowland tropics)

Climate

- Summer: ~30–35 °C (86–95 °F)

- Winter: ~20–25 °C (68–77 °F)

- Humidity: ~70–90%, feels heavy, sweaty

Landscape

- Dense jungle, rivers, wetlands, coastal plains

- Lush plant growth year-round

5. Maya Lowlands (Yucatán Peninsula)

(Southernmost stop)

Climate

- Summer: ~30–34 °C (86–93 °F)

- Winter: ~18–26 °C (64–79 °F)

- Humidity: ~65–85%, sticky, constant sweat zone

Landscape

- Flat limestone plains

- Dense jungle, cenotes instead of rivers

- Thin soil, tricky farming conditions

Population & Top Cities

Where were people living and how packed did the map feel when you zoomed in?

Estimated total population: ~12 million people

Central Mexico alone likely held 3–5 million of those.

Five Major Population Centers

1. Chichén Itzá (Yucatán Peninsula)

Estimated population: 30,000–50,000

This was one of the largest and most influential cities in the northern Maya world. By 1100 AD it was past its peak, but still deeply connected to regional trade, politics, and ritual life.

Why it mattered:

- Reliable access to cenotes (natural underground water sources)

- Major trade networks linking the coast, lowlands, and highlands

- Major religious and ceremonial pull

2. Tula (Central Highlands)

Estimated population: ~40,000

Tula wasn’t just a city, it was a reference point. Even after decline, people talked about it like a gold standard of how cities should be run.

Why it mattered:

- Political influence

- Skilled craft production, especially in stone and obsidian

- A powerful collective memory that shaped later ideas of leadership and order

3. Cholula (Puebla Valley)

Estimated population: ~30,000–40,000

Cholula was busy for one big reason: religion.

Why it mattered:

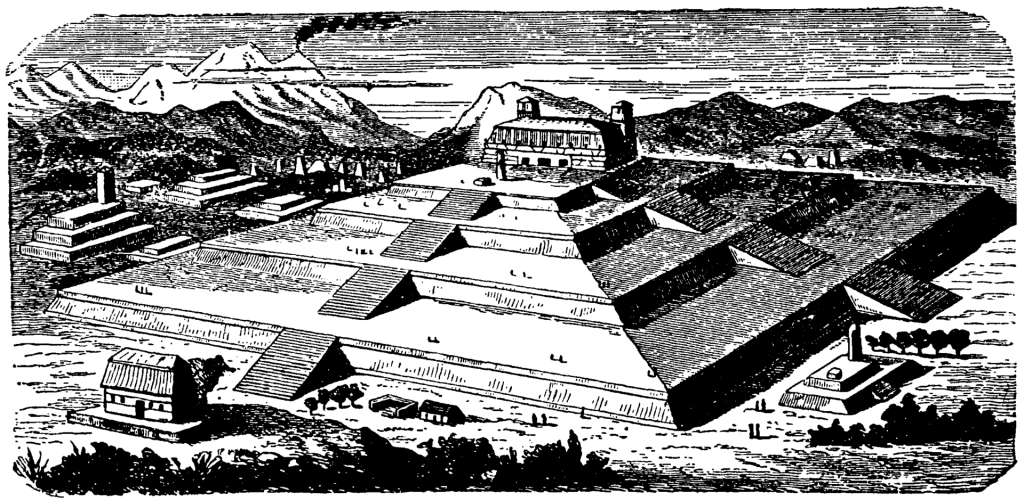

- The largest pyramid by volume in the world

- The Great Pyramid of Cholula, known in Nahuatl as Tlachihualtepetl (the constructed mountain) hides in plain sight. It doesn’t tower dramatically like the pyramids in Egypt, and that’s part of the trick. Built up layer by layer over centuries, this temple complex is actually the largest pyramid in the world by volume, and the largest single monument ever constructed by humans. Its base stretches roughly 300 x 315 meters (984 x 1,033 ft), and while it rises only about 25 meters (82 ft) tall, its sheer mass adds up to more than 4.45 million cubic meters, nearly double the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza. Traditionally associated with Quetzalcoatl, the pyramid wasn’t about reaching the sky so much as becoming the landscape itself, a sacred mountain made by human hands, meant to anchor gods, rituals, and everyday life all in one place.

- Long-term pilgrimage activity

- Markets serving locals and travelers alike

4. Uxmal (Puuc Region, Yucatán)

Estimated population: ~20,000–25,000

Uxmal was past its peak by 1100 AD, but still very much inhabited and relevant.

Why it mattered:

- Smart water management.

- Uxmal sits in a region that looks lush, but ancient residents faced long dry seasons with no rivers or cenotes to rely on, and limestone bedrock that drains water quickly underground. Their solution wasn’t finding water, it was learning how to store every drop of rain.

- They built chultuns, large underground cisterns carved into limestone to collect rainwater

- Carefully shaped plazas and rooftops that funneled rain into storage

- Uxmal sits in a region that looks lush, but ancient residents faced long dry seasons with no rivers or cenotes to rely on, and limestone bedrock that drains water quickly underground. Their solution wasn’t finding water, it was learning how to store every drop of rain.

- Strong regional identity

- Impressive architecture

5. Mitla (Oaxaca Valley)

Estimated population: ~10,000

Smaller than the mega-cities, but powerful in a different way.

Why it mattered:

- A religious and elite center

- Renowned for its intricate stone mosaics and architecture

- Deep connections to ancestors, burial traditions, and ritual authority

Health

How long did people live, how did they heal, and what everyday dangers shaped their bodies?

Health in 1100 AD Mexico wasn’t about hospitals, checkups, or specialists you visited once something went wrong. Health was something you maintained, through bathing, herbs, rest, ritual, and community care, not something you outsourced.

If you made it through childhood, your odds improved a lot. Many adults lived into their 40s–50s, and some into their 60s

Estimated child survival: Roughly 60–70% of children reached adulthood

What Were the Biggest Health Risks?

Common dangers:

- Infectious diseases (especially gastrointestinal and respiratory)

- Parasites

- Malnutrition during droughts or crop failures

- Work injuries (cuts, strains, broken bones)

- Childbirth complications

- Water-related illness if sources were contaminated

Violence existed, yes, but for most people, illness and environment were far more dangerous than warfare.

Medicine & Healing

Healthcare absolutely existed, it just didn’t look like a modern clinic with white walls and waiting rooms. Healing was local, relational, and deeply informed by experience.

Healers included:

- Midwives (experts in pregnancy, birth, postpartum care)

- Herbal specialists who knew plants deeply

- Bone-setters and wound healers

- Ritual healers who treated illness as imbalance, not just injury

Later sources like the Florentine Codex describe hundreds of medicinal plants, with uses for:

- wounds

- fevers

- stomach illness

- pain

- reproductive health

This wasn’t guesswork. It was trial, error, memory, and teaching passed down carefully.

Childhood & Parenthood

What was it like to be a kid—or raise one?

In 1100 AD Mexico, childhood wasn’t a waiting room for “real life.” It was training for it. And parenthood wasn’t about optimization or gentle parenting philosophies, it was about preparing kids to survive, contribute, and belong in a world that didn’t slow down for anyone.

Birth: Entering the World Correctly

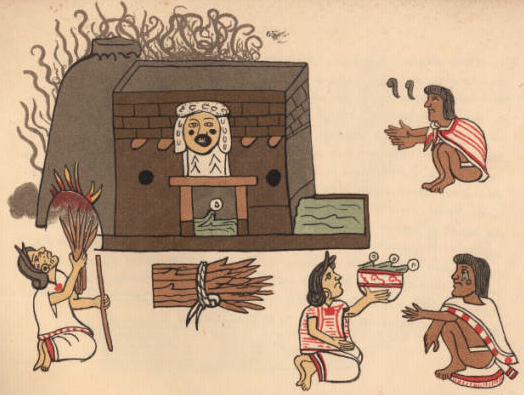

This image from the Codex Mendoza (created around 1535–1550, recording much older Nahua practices) shows how a baby was welcomed into the world properly, with water, words, food, community, and intention.

According to 16th-century accounts, this ceremony usually happened on the fourth day after birth. Before sunrise, family gathered inside the home. There was food. There were witnesses. This wasn’t private, a child arrived into a community, not just a household.

At the center stands the midwife, holding the baby. She wasn’t only a birth attendant, but a ritual expert trained to guide new life safely into the human world. She worked alongside a tonalpouhqui, a calendar specialist who identified the child’s day sign, a framework adults would use throughout childhood to understand temperament, ability, and struggle.

The image reads like a sequence. Dotted lines show the midwife lifting the baby from the cradle and carrying them to a clay vessel of water set on a woven mat. Her footprints move counterclockwise, a deliberate choice. In Nahua ritual practice, moving against the sun’s path was used during moments of danger and transition, helping restore balance after childbirth.

Objects placed on the mat signal how society imagined the child’s future role. Boys are associated with tools, shields, and knowledge. Girls with brooms, baskets, and spindles, not lesser symbols, but the tools that sustained households and food systems.

The baby is then washed through a series of water rites, cleansing the mouth, heart, head, and body. These actions echoed a wider belief system found in Nahua ritual almanacs, where gods shaped human destiny through four core acts: piercing, lifting, linking, and nourishing. What mattered wasn’t prediction, but alignment, placing the child correctly within the world.

The ritual shifts depending on the child. A boy is lifted toward the sky four times, calling on solar strength. A girl is turned toward the cradle and the mother goddess, asking for endurance and care. Only after this does the child receive a name, tied to the moment of birth and the rhythm of the calendar.

Off to the side, children sit eating beans. That detail matters. The beans aren’t symbolic offerings, they’re everyday, nourishing food. Their presence tells us the household is functioning again. The danger has passed far enough that people can eat. Life continues while a new life is welcomed.

That context matters because in Nahua thought, childbirth was compared to warfare. A woman who gave birth was understood to have fought a battle against pain, blood loss, and death. Survival of both mother and child was never assumed.

Breastfeeding & Early Childhood

How long were babies nursed and what did that mean for family life?

In 1100 AD Mexico, breastfeeding was the norm, not a parenting ideology, but the expected start of life. Based on later Nahua descriptions (including those recorded in the Florentine Codex), children were typically nursed for 2-4 years, with around 3 years being very common.

That length might sound surprising today, but it was practical. Extended breastfeeding supported nutrition and immunity during the most dangerous early years, helped space pregnancies, and offered emotional regulation in busy, communal households.

Breastfeeding also didn’t mean children consumed only milk. As babies grew, soft, mashed foods were introduced gradually. Thin maize preparations like atole appeared alongside nursing, and weaning was slow and flexible, not abrupt. Children often continued nursing while learning to eat solid foods, easing transition and reducing risking while learning to eat solid food, easing the transition and reducing risk.

What It Was Like to Be a Child

Children were everywhere, underfoot, helping, learning, watching. Childhood existed, but it wasn’t long or cushioned.

5 Pros of Being a Child

- Strong sense of belonging: you grew up surrounded by family and neighbors

- Clear expectations: you knew what was expected of you at each age

- Constant skill-learning: farming, weaving, cooking, carrying, selling

- Freedom to play within workspaces: kids learned by doing, not isolating

- Deep connection to ritual and community life: ceremonies marked your growth

5 Cons of Being a Child

- High childhood risk (illness, accidents, food shortages)

- Early responsibility: chores came young

- Strict discipline: correction mattered more than self-expression

- Little personal privacy: life was shared

- Adulthood arrived fast: especially with marriage expectations

Kids weren’t pressured to “be special.” They were expected to be capable.

What Parenting Looked Like

Parenting was shared. Kids didn’t belong to one adult, they belonged to the household and community.

Roles in the Household:

- Mothers: daily caregiving, food prep, textile work, early instruction

- Fathers: farming, craft work, trade, discipline, teaching endurance

- Grandparents & elders: moral instruction, storytelling, childcare, memory-keeping

Discipline & Affection

In Nahua thought, children were deeply valued. Ritual language compared them to jade or young plants, precious, fragile, and full of potential. A child wasn’t disposable or insignificant. They were something meant to be shaped with care.

Affection existed, but it wasn’t indulgent. Care meant feeding, teaching, correcting, and protecting, not shielding children from responsibility. Parents and elders believed their role was to prepare, not pamper. An old proverb warned against raising “fruitless trees”, i.e. people who could not contribute. In a world built on cooperation, that was dangerous.

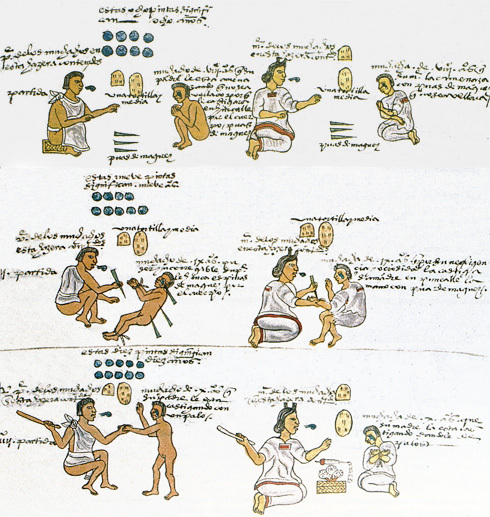

Sources recorded shortly after the Spanish conquest, especially the Codex Mendoza, emphasize obedience, self-control, and proper behavior. Childhood wasn’t about self-expression. It was about learning how to live among others without bringing harm or shame to your household.

The Codex image reads like a visual lesson. First, both a boy and a girl are threatened with maguey thorns. The warning alone mattered. Correction didn’t always require action.

When punishment is carried out, it is gendered. A girl is pierced lightly in the arm by a woman, likely her mother or caregiver. A boy is punished more severely, pierced in multiple places and bound, by a man understood to be his father.

In the final scene, punishment escalates to striking with a rod. The children are shown weeping openly. The image does not hide the emotional weight of correction.

Two things matter here. First, discipline trained children for the roles society expected them to fill. Second, this image reflects idealized norms, not proof that every household punished children this way daily. The Codex Mendoza was created to explain Indigenous life to outsiders, emphasizing order and morality, showing what should happen when discipline failed.

Discipline could be strict, especially as children aged. But the goal wasn’t cruelty. It was shaping character. In a communal world, one person’s behavior could ripple outward, affecting reputation, safety, and survival. Correction wasn’t punishment for its own sake, it was responsibility.

5 Pros of Being a Parent

- Status and respect in the community

- More hands to help as children grew

- Emotional continuity, children carried your memory forward

- Shared labor eased survival

- Participation in ritual life through children’s milestones

5 Cons of Being a Parent

- High emotional risk: child mortality was real

- Constant labor demands: mouths to feed, bodies to protect

- Responsibility for moral behavior: your child’s actions reflected on you

- Limited personal freedom

- Stress during bad seasons: hunger hit families hardest

Pets & Animals

People didn’t keep pets for cuteness alone, but animals still mattered.

Common household animals included:

- Dogs (companionship, protection, sometimes ritual roles)

- Turkeys (food + ritual significance)

- Small animals kept near households depending on region

Animals were part of daily life, fed scraps, shared space, understood as living beings with roles

Leisure & Recreation

How did people rest, play, celebrate, and blow off steam?

Leisure for Adults

Adults didn’t clock out at 5 p.m., but there were real breaks, moments to socialize, compete, drink, dance, and watch the world move.

Popular Adult Pastimes

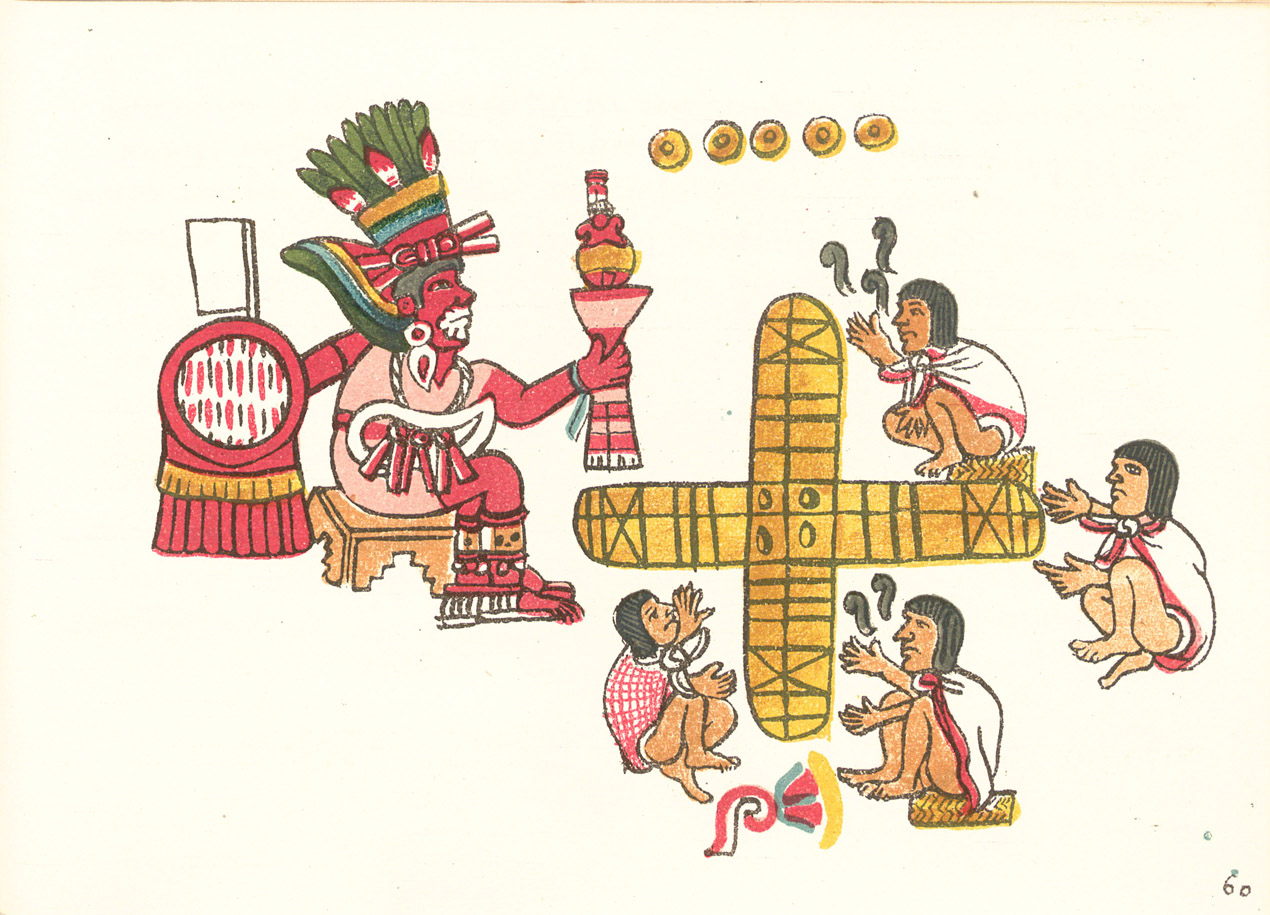

- Board and chance games (like patolli, competitive, loud, social, sometimes high-stakes)

- Music and dance, especially during ritual calendars

- Storytelling and oral performance: history, myth, jokes, warnings

- Drinking ritual beverages in controlled settings (not casual taverns, but community-regulated contexts)

- Watching sports, especially the ballgame (ōllamaliztli), which blended athleticism, ritual, and spectacle.

Festivals, Gatherings & “Events”

Common communal events included:

- Harvest festivals tied to maize cycles

- Religious feasts honoring deities, seasons, or community milestones

- Market days: yes, shopping, but also gossip, flirting, food, and street performance

- Ceremonial dances with costumes, music, and shared participation

Leisure for Children & Families

Children’s Games & Play

- Running and chasing games (very tag-adjacent energy)

- Regional stick-and-ball games (like timbomba) known later among Maya descendants

- Rubber balls for informal play (kids mimicking ulama/ballgame)

- Dolls and figurines, often clay or wood

- Miniature tools and instruments, letting kids imitate adult work

- Riddles, songs, and verbal games passed down orally

Culture, Language & Religion

How people understood the world, spoke to the divine, and expressed meaning through art.

Three Major Cultural Worlds (and how they felt to live in)

1. Central Mexico: Nahua / Toltec-influenced societies

This ceramic vulture wasn’t just decorative, it was cosmic. Birds in Nahua and Toltec thought linked earth to sky, carrying messages between humans and the divine.

Core traits:

- Dense cities and farming communities

- Strong emphasis on order, discipline, and social roles

- Ritual life tied closely to calendars and warfare

- Markets, tribute systems, and neighborhood organization

Life here felt structured and formal, with a strong sense that behavior mattered, morally and cosmically.

2. The Maya World: Yucatán & Southern Lowlands

Core traits:

- City-states rather than one empire

- Heavy focus on astronomy, timekeeping, and writing

- Ritual life tied to cycles of creation and renewal

- Art that emphasized precision, symbolism, and lineage

Living in the Maya world meant being constantly aware of time, days mattered, dates mattered, history mattered.

3. Oaxaca: Zapotec & Mixtec Societies

Carved from glossy tecali stone, this mischievous monkey wasn’t just cute, it carried meaning. Across Mesoamerica, monkeys were linked to creativity, performance, and the arts, admired for their cleverness and expressive behavior.

Core traits:

- Strong lineage identity

- Highly developed stone architecture and geometric art

- Emphasis on burial, ancestors, and sacred places

- Skilled artisans and scribes

This was a world where beauty and legitimacy were intertwined.

Religion Was Not Optional

The universe was understood as alive but unstable. Humans had responsibilities to keep it moving correctly.

Religious life included:

- Many gods tied to rain, maize, fire, death, fertility, war

- Ritual calendars that structured the year

- Taboos governing food, sex, behavior, and speech

- Moral expectations: moderation, respect, balance, restraint

Art: How Meaning Was Made Visible

Art in 1100 AD Mexico was symbolic, intentional, and everywhere.

Common media:

- Stone carving

- Painted manuscripts (codices)

- Murals

- Ceramics

- Textiles

- Featherwork

Language & Literacy

Mexico in 1100 AD was linguistically rich.

Major languages included:

- Nahuatl (Central Mexico)

- Maya languages (Yucatán & southern regions)

- Zapotec and Mixtec (Oaxaca)

Literacy looked different:

- Writing systems used glyphs and pictorial signs

- Codices recorded:

- history

- tribute

- rituals

- calendars

Historical Context

What had recently changed and what pressures were shaping the world people lived in?

Climate Stress & Adaptation

Between 900 and 1100 AD, multiple regions of Mexico experienced periods of drought. Not apocalyptic, but persistent enough to matter.

What that meant on the ground:

- Farming became riskier in some areas

- Migration increased

- Water management mattered more than ever

- Communities leaned harder on ritual and calendar timing

This is one reason you see:

- renewed emphasis on rain rituals

- cities clustering tightly around water sources

- strong social pressure to behave “correctly”

When the weather feels unreliable, belief systems get louder.

New Technologies, Slowly Spreading

Small but loud, this metal bell turned movement into sound. Worn on bodies, costumes, or regalia, tzilinilli transformed walking, dancing, and ritual into something audible

Not everything was stress and loss. Some real advancements had taken root since 900 AD.

One big one: metalworking.

- Copper and copper alloys began appearing more regularly in western Mexico

- Metal wasn’t replacing stone tools yet

- But it showed up in:

- bells

- ornaments

- prestige items

This wasn’t industrial change, it was symbolic change. New materials meant new sounds, new aesthetics, new status markers.

Music & Instruments

What did daily life sound like—and when people gathered, what filled the air?

Instruments You’d Hear

Percussion (the backbone)

- Huehuetl: a tall, upright drum carved from wood, played with hands

- Teponaztli: a horizontal slit drum that produced two tones

- Hand drums of various sizes

Drums weren’t just instruments, they were sacred objects, often carved and named. Yup, like name named, some ceremonial drums were not treated as interchangeable instruments. Because of that, they weren’t anonymous tools. They were named, remembered, and sometimes spoken to or addressed in ritual language.

Not every drum in someone’s courtyard had a name, but temple drums absolutely could, because their sound was believed to move gods and time itself.

Wind Instruments (the voices)

- Clay flutes (often shaped like animals or people)

- Ocarinas

- Whistles

- Conch shell trumpets used to call attention or open ceremonies

Rattles & Shakers (movement makers)

- Ayacachtli (seed or shell rattles)

- Ankle rattles worn by dancers

Music, Dance, and Education

Mexica society had gendered education paths:

- Boys trained for roles as priests, administrators, and warriors

- Girls learned domestic and household skills from their mothers

But all children learned music and dance. Regardless of gender, children were taught songs, ritual dances and how to move in time with others. Music and dance were considered essential social skills, not optional talents. You couldn’t participate fully in ritual life without them. Messing up a ritual song wasn’t embarrassing, it was cosmically serious. Music helped train people to act in harmony with others.

What Would a “Playlist” Sound Like Today?

We obviously don’t have recordings from 1100 AD. But we do have modern reconstructions using traditional instruments, archaeological evidence, and Indigenous continuity.

- Jorge Reyes – “Teponaztli”

Deep percussion inspired by Central Mexican ritual drums - Xochipilli Ensemble – “Huehuetl y Ayacachtli”

Focuses on rhythm and movement, very ceremony-forward - Luis Delgado – “Música Prehispánica: Ceremonia”

Experimental but grounded in documented instruments - Tlen Huicani – “Sonidos del México Antiguo”

Uses wind instruments and percussive layers - Xquenda – “Danza Ritual”

Emphasizes dance rhythms and communal pacing

Media You Can Watch or Read Today

Continue your journey with these books and movies.

Adults

Movies

- Apocalypto (film)

Language: English (original, with recreated Maya dialogue); Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish subtitles available widely

A visceral historical drama that follows a Maya hunter trying to save his family after his village is raided. packed with action, ritual, and jungle life set just before Spanish contact. - Retorno a Aztlán (1989)

Language: Spanish (original); Subtitled: varies by release

A mythic drama set around the legendary return to Aztlán, shot in nahuatl, a rare cinematic plunge into Indigenous language and worldbuilding.

Books & Reading

- Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs – Camilla Townsend

Language: English

A sweeping, indigenous-centered history of the Mexica/Aztec world, told through voices and sources that existed outside the colonial European viewpoint. - El corazón de piedra verde (The Heart of Jade) – Salvador de Madariaga

Language: Spanish (original); Translated: English editions exist

A classic historical novel set in the late pre-Columbian era that brings Aztec society to life through rich characters and thoughtful drama.

Kids

TV Shows & Movies

- Las Leyendas (Netflix)

Language: Spanish (original); Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 8–12

This is a favorite for a reason. It’s spooky-but-not-too-scary, funny, and rooted in Mexican folklore. The kids go on supernatural adventures that pull in Indigenous legends and monsters, so it sneaks history in without feeling like homework. Great if your kid likes mystery, humor, and a little creepiness without nightmares. - Maya and the Three (Netflix)

Language: English (original); Dubbed: Spanish available

Ages: 7–12

This one is fantasy, not a history lesson, but the visual world is deeply inspired by Mesoamerican cultures. Strong female lead, epic quests, gods, warriors, and lots of heart. If your kids love action stories and you want something that feels culturally rich and empowering, this is a win. - Legend Quest: Masters of Myth (Netflix)

Language: Spanish (original); Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 8–12

Same universe as Las Leyendas, but a little more action-heavy. It leans hard into Mexican mythological creatures and folklore. Think: monsters, magic, jokes, and teamwork. If your kid liked Las Leyendas, this is the natural next step. - Dora the Explorer

Language: English & Spanish bilingual; Dubbed: Spanish versions available

Ages: 3–6

This is a classic for a reason. While it’s not ancient-history focused, Dora gently introduces Spanish language, Mexican landscapes, animals, and cultural cues in a way that feels normal and friendly. Think of it as cultural familiarity, not a history lesson, perfect groundwork before deeper stories later.

Movies

- The Book of Life (2014)

Language: English (original); Dubbed: Spanish available

Ages: 6–10

This is technically set later, but it’s fantastic for introducing kids to Mexican ideas about death, remembrance, and the afterlife in a gentle way. Bright colors, music, and a love story that stays kid-friendly. Good if you want culture without scariness.

Books

Picture Books / Early Readers

- My First Book of Aztec Mythology

Language: English

Ages: 4–7

Very gentle, simplified retellings of Aztec myths with friendly illustrations. This is one of those “flip through together and talk about pictures” books, great if your kid is curious but not ready for heavy topics. - The Day It Rained Tortillas

Language: English; Spanish editions available

Ages: 4–7

Not ancient, but wonderfully grounded in Mexican daily life, food, and imagination. - The Princess and the Warrior: A Tale of Two Volcanoes – Duncan Tonatiuh

Language: English; Spanish edition available

Ages: 5–9

Beautiful illustrations inspired by pre-Hispanic art styles. It retells an Aztec legend in a gentle, romantic way. This is a great “read-together at bedtime” book if your kid likes myths and legends. - Sun Stone Days – Susan Mark & David Diaz

Language: English

Ages: 6–10

This book walks kids through daily life in the Aztec world, food, games, family, beliefs, without being overwhelming. It’s calm, informative, and very approachable. Perfect if your child is curious and asks lots of “why” questions.

Chapter Books / Middle Grade

- The Storm Runner – J.C. Cervantes

Language: English; Spanish editions available

Ages: 9–13

Modern kids + ancient Mesoamerican gods = action-packed adventure. It’s fast, funny, and myth-heavy. Not historically set, but it introduces gods, cosmology, and cultural ideas in a way that sticks. Great for Percy Jackson fans.

Would you feel grounded by this way of life, or overwhelmed by the work and rituals that filled each day? Life in 1100 AD Mexico asked a lot of people, but it also gave meaning in return. Let me know what stood out to you most in the comments or tag me on social.

Leave a comment