Step into a different time. In this post, we step into Mexico around 1300 AD a world of lake cities and jungle towns, where the day began with cool air and sweeping patios, and ended with shared meals and firelight. We’ll explore what daily life actually looked like, from sunrise routines and family rhythms to what was simmering on the comal and echoing through the streets.

Just so we’re all on the same page. Please ensure you’ve made yourself acquainted with my disclaimer

Home Life

Step into their house: how big was it, what did it look like, and how did people sleep or stay clean?

What a “normal” house looked like

Picture a one-room house, rectangular, about 20–30 m² (215–320 sq ft). No hallways, no bedrooms, no bathrooms, just one shared space where life happened. Walls were adobe or wattle-and-daub, the floor packed earth, cool under your feet in the morning.

Typical layout included:

- Rooms: technically one, but mentally divided by habit and use

- Roof: thatch or flat timber

- Yard: small patio for cooking, washing, grinding maize

Sleeping, dreaming, and the art of the nap

People slept on petates (woven reed mats) rolled out at night and stacked during the day. No pillows as we know them, maybe a folded cloth or arm. You slept with the sun, not a clock.

Rest looked like:

- Sleep schedule: sunset to sunrise, more or less

- Beds: petates on the floor, sometimes animal skins on top

- Blankets: cotton mantas in cooler regions

- Naps: totally normal, especially midday, after food and heat

Bathing, cleanliness, and staying human

No bathrooms, but cleanliness mattered. People bathed often, sometimes daily, using water from canals, rivers, or household jars. Sweat, dust, and smoke were part of life, so washing was practical, not indulgent.

Self-care wasn’t luxury. It was maintenance. You cared for the body because it carried your spirit.

Sweeping mattered too. Every morning, patios and floors were swept clean, not just for hygiene, but spiritually. Clearing dust meant clearing bad energy. Order in the home meant balance in the world.

Everyday hygiene tools included:

- Soap: natural plants like copalxocotl and roots

- Tools: gourds, clay bowls, hands (the original multitool)

- Teeth & hair: chewed sticks, water, oils

And yes, temazcales (sweat baths) existed. Hot stones, steam, herbs. For healing, childbirth recovery, or just feeling human again.

If you want to see how these practices worked in motion, the sweeping, the washing, the rhythm of care, this video offers a helpful reconstruction and visual reference:

Objects that mattered inside the home

No “appliances,” but the house was full of everyday tools.

- Metate & mano: heavy volcanic stone, cool and rough

- Comal: clay griddle, blackened from years of use

- Ollas: wide-bellied clay pots for water and beans

- Household shrine: usually small, gods lived with you, not apart

Fashion & Beauty Standards

What did people wear and what did society expect them to look like?

Clothing, the basics:

Most garments were rectangular pieces of fabric, wrapped, tied, or knotted into place.

- Women: huipil (sleeveless tunic) + long wrap skirt

- Men: maxtlatl (loincloth) + tilmatli (cloak)

- Children: very minimal, often just a small cloth until older

- Gendered dress: Children dressed simply until social roles mattered. Gendered clothing grew with responsibility, not at birth.

- Shoes: leather or fiber sandals (cactli), mostly outdoors only

Silhouettes were straight and practical. Fabric moved when you walked, breathed when you worked, and aged with you. Clothing wasn’t replaced often, it was repaired, reused, respected.

Materials, texture, and color

Most people wore maguey fiber if they had to and cotton if they could. Cotton was softer, lighter, and harder to produce. It quietly signaled status. Color did too.

- Fabrics: cotton (elite), maguey/ayuate (common)

- Dyes: cochineal red, indigo blue, plant yellows

- Decoration: woven patterns, embroidery, fringed edges

- Fastening: knots, belts, shoulder ties

Bright color wasn’t frivolous, it was labor. You wore someone’s hours on your body, which meant an increase in cost.

Hair, grooming, and everyday beauty

Beauty was not about excess. It was about order and care. Hair especially carried meaning. It was not just aesthetic. It was moral.

- Women’s hair: long, braided, sometimes wrapped with thread

- Men’s hair: medium length; some shaved styles depending on region

- Facial hair: sparse genetically

- Cosmetics: mineral pigments, charcoal, clays

- Scents: flowers, resins, smoke

Messy hair could signal grief, punishment, or ritual transition. Order on the head reflected order in the soul.

Jewelry, body art, and adornment

Common forms of adornment included:

- Materials: jade, turquoise, shell, obsidian, gold (rare)

- Piercings: ears common; nose or lip for elites

- Feathers: big deal, bright, symbolic, prestigious

- Body paint: temporary, ritual, regional

Adornment told people who you were, where you came from, and what you’d earned. No introductions needed.

Bodies, beauty ideals, and gender

Beauty standards leaned toward health, strength, and balance.

- Average height:

- Men: ~160 cm (5’3″)

- Women: ~148–150 cm (4’10″–4’11”)

- Body type: compact, strong, functional

Body Modification: shaping identity, not rebelling

Before we jump to “wow, that’s extreme,” pause. In 1300 Mexico, modifying the body wasn’t about shock, it was about belonging, beauty, and destiny. Your body was a canvas the community helped you shape.

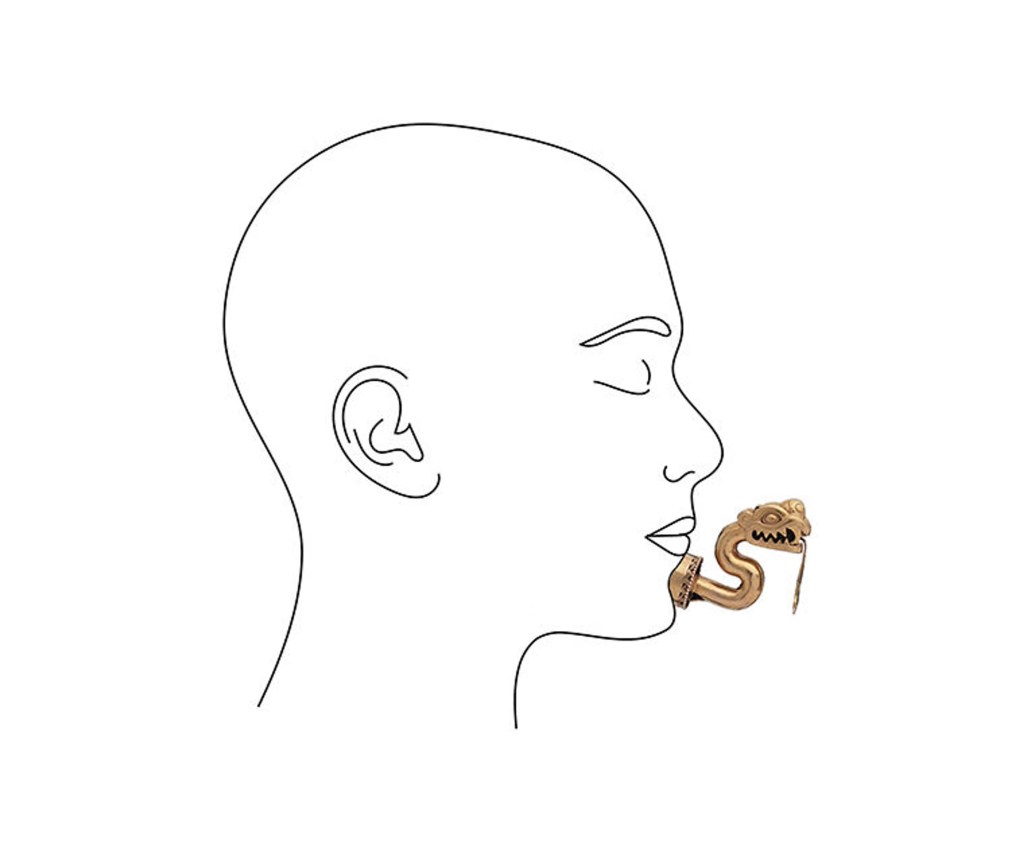

Piercings:

Piercing was common, especially ear piercings, and almost expected.

- Ears: widely pierced across genders

- Nose & lip (labret): more elite, often jade or obsidian

- Materials: bone, shell, stone, later gold

- Meaning: age, status, ritual readiness

You didn’t pierce just because. It marked moments, growing up, earning status, stepping into responsibility. Honestly, not that different from how we treat milestones today… just fewer Claire’s kiosks.

Head shaping

Okay, here’s the one that makes modern people clutch their pearls: cranial modification. Some families gently shaped infants’ heads using boards or cloth bindings while the skull was still soft.

- Shape ideal: elongated or flattened forehead

- Started: infancy only

- Pain: minimal if done properly

- Why: beauty, lineage, spiritual alignment

This wasn’t random or cruel. It was careful, controlled, and culturally admired. A shaped head could signal refinement and noble heritage. And before we judge, every culture edits the body. We just pretend ours is “natural.” When you zoom out, head shaping in 1300 Mexico isn’t stranger than waist trainers, braces, or six-step skincare routines. The tools change. The pressure to belong doesn’t.

Tattoos, scarification, and teeth

These practices existed, but they were not universal.

What we know:

- Tattoos: associated with devotion, warfare, or rites

- Placement: arms, chest, sometimes face (rare)

- Scarification: limited, symbolic

- Dental modification: elite practice

- Inlays: jade or stone embedded in teeth

Not all body markings in art were permanent. Some were paint. What mattered was meaning, not permanence.

Imagine smiling and your teeth sparkle with jade. Subtle? No. Intentional? Absolutely.

How society saw modified bodies

A modified body wasn’t “altered” it was completed. These practices aligned the physical self with cosmic order, family identity, and social role.

- Unmodified bodies: normal, especially among commoners

- Modified bodies: admired, not mandatory

- Gendered differences: yes, but overlapping

- Children: changes guided by elders, not personal choice

The community shaped the body with purpose.

Diet & Daily Meals

Explore what they grew, hunted, cooked, and craved.

How they thought about food

Food wasn’t pleasure first, it was relationship. Relationship to the land, the seasons, the gods, and the body. Eating well meant staying balanced, strong, and able to work; craving wasn’t sinful, but excess was suspicious.

What actually made up the diet

This was a maize civilization, full stop. Everything else orbited around it.

- Staple foods:

- Maize (tortillas, atole, tamales)

- Beans (boiled, sometimes mashed)

- Squash & greens (quelites, pumpkin, nopales)

- Chiles (fresh, dried, ground into sauces)

- Turkey, fish, insects, eggs, wild game

- Seasonal: prickly pear, sapote, berries

- Water, atole (thin maize porridge), herbal infusions

How much of life revolved around food

A lot. Easily half the day, depending on season.

Food shaped the day instead of squeezing into it. Fields were tended early and late. Maize was ground daily. Cooking was slow, constant, and visible. Trade happened when markets allowed.

Tasks existed because food needed to happen.

When and what they ate

Here’s the daily rhythm, more or less, flexible, not rigid:

A typical day looked like this:

- Early morning: a light start like atole or a leftover tortilla with chile

- Midday: the main meal with tortillas, beans, vegetables, and chile sauce

- Afternoon: a small bite such as fruit, roasted seeds, or a drink

- Evening: a lighter repeat of tortillas and beans or leftovers

The midday meal mattered most. It fueled the body through heat, labor, and long afternoons.

How meals actually happened

There were no tables. People ate on the ground, usually on woven reed mats, sometimes near a low platform or packed earth floor. Cooking happened nearby, often in the same space or just outside.

Food vessels were placed centrally, not individually plated. There were no forks, knives, or spoons. Hands were the primary tool, and tortillas did most of the work. They acted as scoops, wraps, and spoons all at once. Liquids were sipped from clay cups or small bowls.

There were no courses. Food was eaten all at once, combined freely, and repeated in steady patterns. The rhythm rarely changed: Tear tortilla. Scoop beans or vegetables. Add chile. Eat. Repeat.

Modern people struggle with repetition. For them, stability was the goal.

Eating together

Children ate with adults, the same food in smaller portions. Very young children were given softened food or dipped tortillas. There was no separate table and no kids’ menu.

Meals were where children learned how to eat, how to behave, and how to belong. Culture was absorbed through watching, copying, and repetition.

OG VERSION

- Morning

- Masa–Amaranth Porridge: Nixtamalized maize ground on a metate and cooked with water, thickened with ground amaranth. Soft, warm, and sustaining rather than smooth or sweet. Sometimes lightly salted, often completely plain.

- Drink: Water

- Snack

- Roasted Amaranth or Maize Kernels: Dry-roasted seeds or kernels prepared earlier and carried from home.

- Drink: Water from gourds or clay jars

- Main Communal Meal

- Maize–Amaranth Flatbreads: Hand-formed flatbreads made from nixtamalized maize mixed with ground amaranth, cooked on a hot clay comal. Thicker and heartier than tortillas, used as both food and utensil.

- Boiled Beans: Slow-cooked earlier in the day and kept warm. Eaten whole or pressed into a coarse mash.

- Squash & Nopales: Seasonal squash or squash blossoms paired with young nopales. Nopales are dry-cooked first on the comal to release moisture and reduce slime, then lightly salted or combined with squash.

- Chile Sauce, Ground on a Metate: Chiles and water ground into a thin sauce, sometimes thickened with amaranth. Added bite by bite, not poured.

- Drink: Water or thicker atole, depending on labor demands

- Sweet Item (Occasional, seasonal, not daily)

- Amaranth with Honey: A small amount of amaranth mixed with honey when available.

- Drink: Water or cacao if eaten in ritual contexts

MODERN VERSION

Contemporary Mexican-Inspired Menu

- Breakfast

- Stone-Ground Corn Polenta with Amaranth: Slow-simmered corn polenta enriched with toasted amaranth, finished silky and spoonable. Served with browned butter, smoked honey, and flaky sea salt.

- Drink: Warm corn latte with vanilla and toasted grain notes

- Snack

- Amaranth–Chile Crunch: Puffed amaranth tossed with ancho chile, citrus oil, and sea salt. Light, crisp, and addictive.

- Drink: Sparkling mineral water with citrus peel

- Dinner

- Charred Nopal & Summer Squash Flatbread Tacos: Warm maize-amaranth flatbreads layered with fire-charred nopales and squash, silky black bean purée, and a warm chile sauce thickened with toasted amaranth.

- Drink: Chilled corn agua fresca with a hint of citrus

- Dessert

- Amaranth Honey Cake: A restrained amaranth sponge soaked lightly in honey syrup, designed for sharing — warm, nutty, and not overly sweet.

- Drink: Chilled cacao drink with gentle chile warmth

Climate & Environment

How did geography and weather shape daily life?

Mexico in 1300 was not one climate. It was many Mexicos stitched together. Mountains, coasts, jungles, and deserts shaped how people moved through the day and what daily life made possible. If you want to understand how people lived, you start with the land.

Climate shaped more than food and housing. It shaped time itself. When the air was hot and heavy, life slowed down. When mornings were cold, work began early. Mexico’s famous sense of “ahorita” makes more sense when you realize that time here has always been negotiated with weather, light, and heat.

1. Northern Arid & Semi-Arid Lands (Chichimeca regions)

Climate

- Summer: ~35–40 °C (95–104 °F), very dry

- Winter: ~5–15 °C (41–59 °F), cold nights

- Humidity: low, often under 30%

Landscape

Wide open desert and scrubland. Mesquite, cactus, rocky soil, long distances between water sources.

2. Central Highlands (Valley of Mexico & surrounding plateaus)

Climate

- Summer: ~22–26 °C (72–79 °F)

- Winter: ~5–15 °C (41–59 °F), chilly mornings

- Humidity: moderate, ~40–60%

Landscape

High-altitude basin surrounded by mountains and volcanoes. Lakes, wetlands, fertile soil. Think cool mornings, strong sun by noon.

3. Gulf Coast Lowlands (Veracruz & coastal plains)

Climate

- Summer: ~30–35 °C (86–95 °F)

- Winter: ~20–25 °C (68–77 °F)

- Humidity: high, often 70–90%

Landscape

Flat, lush, green. Rivers, swamps, thick vegetation. Everything grows fast — including mosquitoes.

4. Southern Maya Lowlands (Yucatán Peninsula)

Climate

- Summer: ~32–38 °C (90–100 °F)

- Winter: ~22–28 °C (72–82 °F)

- Humidity: very high, 75–95%

Landscape

Dense jungle over limestone bedrock. No surface rivers, water came from cenotes and underground systems.

5. Pacific Coast & Southern Foothills (Oaxaca to Guerrero)

Climate

- Summer: ~30–34 °C (86–93 °F)

- Winter: ~18–25 °C (64–77 °F)

- Humidity: moderate to high, ~60–80%

Landscape

Coastal plains rising quickly into mountains. Beaches, mangroves, then forests. Diverse ecosystems stacked close together.

Population & Top Cities

Where were people living and how many were there?

By 1300 AD, Mexico wasn’t sparsely populated or “waiting to be settled.” It was busy, layered, and deeply organized.

Scholars estimate about 15–20 million people lived in what we now call Mexico at this time. That’s more than many European regions had then. So yeah, it was crowded.

What did “big” even mean in 1300 AD

Before zooming in on specific cities, it helps to reset expectations.

Around 1300 AD, most cities in the world were small by modern standards. Urban life existed, but cities with over 100,000 people were rare. Cities over 200,000 were exceptional.

This matters, because Mexico did not just have cities. It had cities that ranked among the largest on Earth.

Global largest cities, c. 1300 AD

Here is the rough global picture, using best historical estimates:

- Hangzhou: ~500,000–800,000

- Cairo: ~400,000–500,000

- Constantinople: ~400,000

- Delhi: ~300,000–400,000

- Tenochtitlan: ~200,000–250,000

Let that settle for a moment.

Tenochtitlan was not big for the Americas.

It was big for the world.

What about Europe at the same time

This is usually where people pause.

Around 1300 AD:

- Paris: ~200,000 people and was one of Europe’s largest cities

- London: ~80,000–100,000

- Florence: ~90,000

- Rome: ~50,000

So yes, Tenochtitlan was likely larger than London and roughly on par with Paris.

And unlike many European cities of the time, it had planned neighborhoods, regulated markets, clean water infrastructure, and canals instead of open sewage.

Top Mexican Cities

Tenochtitlan

- Estimated population: ~200,000–250,000

- Why it mattered: political, religious, economic powerhouse

Built on islands in Lake Texcoco, Tenochtitlan ran on canals, causeways, and chinampas. Water moved through the city intentionally. Food was grown within the urban system itself. Neighborhoods were organized and maintained.

Texcoco

- Estimated population: ~30,000–50,000

- Why it mattered: intellectual and legal center

Texcoco was known for scholarship, poetry, and law. Elites sent their kids here to learn how to rule properly. Think think-tanks, but with feathers and stone.

Chichén Itzá

- Estimated population: ~35,000–50,000

- Why it mattered: ritual, trade, astronomy

By 1300, Chichén Itzá wasn’t at peak power, but it still mattered. Pilgrims came. Traders passed through. Sacred spaces don’t stop being important just because politics shift.

Mayapán

- Estimated population: ~12,000–17,000

- Why it mattered: political capital of the northern Maya

Mayapán was compact, walled, and strategic. Less grand than earlier Maya cities, but very intentional. Power here was centralized and controlled.

Tula

- Estimated population: ~30,000–40,000 (declining by 1300)

- Why it mattered: legacy and symbolism

Tula wasn’t the powerhouse it once was, but its cultural weight lingered. Later societies referenced it constantly — like quoting an old empire to legitimize yourself.

Economy & Jobs

How did people earn a living, and was money even used?

Let’s clear something up right away. Yes, there was money, but not like we think of it today.

This was not a cash economy and it was not pure barter either. Most daily exchange worked through direct trade, but certain goods functioned as standardized currency, especially in markets and long-distance trade.

Both systems existed at the same time, and people understood exactly how they worked.

- Cacao beans: small purchases, everyday transactions

- Cotton cloth (quachtli): larger payments, tribute, wages

- Copper bells & tools: high-value exchange

Prices were widely understood. No haggling chaos. A tomato didn’t cost “whatever.” It cost this many beans. Simple.

Markets: the economic heartbeat

Markets ran daily or weekly, depending on city size. They were regulated, loud, social, and fair with officials watching scales and behavior.

You could buy food, tools, cloth, pottery, labor, and services. But markets were not free-for-alls. They were regulated public spaces.

Markets as public infrastructure

Markets were the economic heartbeat of cities. They ran daily or weekly, depending on size.

You could buy food, tools, cloth, pottery, labor, and services. But markets were not free-for-alls. They were regulated public spaces.

In large markets, especially places like Tlatelolco, appointed officials monitored transactions all day. We know this from Indigenous accounts later recorded in the Florentine Codex.

Their role was straightforward:

- monitoring weights and measures

- enforcing agreed-upon prices

- settling disputes immediately

- penalizing fraud or short-changing

If you cheated, it was not buyer beware. It was your reputation on trial.

Trust, enforcement, and consequences

What happened if someone cheated depended on how serious the offense was.

Minor violations could lead to public scolding or confiscation of goods. Repeat offenses could mean removal from the market. Severe fraud could bring corporal punishment or legal consequences.

Markets were social spaces. Being banned was not just an economic loss. It meant losing trust, connections, and future customers. Social shame did much of the policing.

Fairness was not optional. It was expected.

Work, class, and daily stability

Broad social categories included:

- Elites, such as nobles, priests, landholders, and top merchants

- Commoners, including farmers, artisans, and laborers

- Enslaved people, whose status was real but not permanent or hereditary

Most people lived what we might call stable subsistence. Not wealthy, not starving. Fed, housed, and constantly busy.

Could people move up or down

Yes, more than people expect.

Military success could elevate status. Skilled artisans could gain prestige. Long-distance merchants could rise significantly.

Failure, debt, or political shifts could push someone down just as quickly.

Status was not frozen at birth, but it was not fully fluid either. Movement existed, but within limits.

Enslavement and obligation

Let’s take a breath before this word does its modern damage. Slavery existed, yes. But it worked under a completely different moral and social logic than the racial, hereditary slavery most of us picture. Same word, very different system.

This was a system of status loss, not total erasure.

Who became enslaved or tlacohtin (‘bought ones’)

People did not become enslaved randomly. It usually happened through specific circumstances:

- debt that could not be repaid

- criminal punishment

- captivity through warfare

- self-sale during extreme hardship such as famine or disaster

Importantly, people were not born enslaved. That alone changes how the system functioned.

What enslavement actually looked like

Enslaved people were socially recognized humans with rights, even while unfree.

They typically:

- lived in households or worked specific labor roles

- ate the same food as others in the household

- could marry freely

- could own personal property

- could buy their freedom

Was it permanent

Usually, no.

Enslavement was often temporary. Debt-based enslavement ended once repayment was met. Captives could be ransomed or reintegrated. Children of enslaved people were free.

Some people did remain enslaved for life, but permanence was not the default.

Limits and abuse

Abuse existed. Power imbalance was real. Legal protections were not always enforced.

But cruelty was not celebrated. Society expected limits. Owners who mistreated enslaved people could face social or legal consequences.

Selling labor to survive

One of the most misunderstood practices was voluntary enslavement or debt labor.

In moments of crisis, people could sell their labor to avoid starvation, protect family members, or survive a bad year. This was seen as pragmatic, not shameful.

Labor contracts often lasted days, weeks, or seasons. Work included agriculture, carrying loads, or domestic labor. Food and basic housing were provided.

Debt labor was not inherited by children. Debts could be paid off early. You did not lose your name, identity, or future.

You did not become property in the modern sense. You became obligated.

A note on prostitution

Sex work existed in this Mexico at this time, and it sat on the same social edge as debt labor and other forms of obligation.

Prostitution was not primarily framed as sin. Sex workers were often framed as people who absorbed excess desire so that social order could remain intact. That’s not praise, but it is functional logic. It was understood as a regulated social role, often tied to economic survival, ritual contexts, or specific social categories. In some cases, it was associated with temples or formalized spaces. In others, it functioned as urban labor.

People did not become prostitutes because they were morally fallen. They became prostitutes because they needed to eat, pay debts, or survive instability.

Health

Explore life expectancy, healthcare practices, and common dangers.

Health in 1300 Mexico wasn’t about living forever, it was about staying in balance. Balance between hot and cold, work and rest, body and spirit. People expected illness, injury, and death to be part of life, but they didn’t face them passively. Care was practical, communal, and constant.

Life expectancy

Life expectancy depended heavily on surviving childhood.

If you made it past the early years, many people lived into their 50s or 60s, sometimes longer.

- Childhood survival:

- Infant mortality (under 1 year): ~20–30%

- Mortality under age 5: ~30–40%

- Survival to adulthood: ~60–70%

Healthcare, healing, and balance

Medicine was not one thing, it was layered.

Mesoamerican healers weren’t guessing, they knew their stuff. Across Nahua and Maya medical texts, we see detailed use of plants and treatments for swelling, infections, urinary problems, kidney stones, gout, wounds, and fractures. This was not guesswork. It was accumulated experience.

Modern historians back this up: ticiotl (Aztec medicine) was a full-on medical system, not folk remedies thrown together. It ran on a complex blend of religion, astronomy, divination, and the hot/cold balance.

Healing also addressed imbalance. Grief, fear, anxiety, and shock were understood as conditions that could weaken the body just as much as physical injury. Treatment focused on restoring harmony rather than isolating the sick. You were not expected to heal alone. Recovery meant reintegration into daily life, not separation from it.

- Ticitl: trained healers (men and women)

- Midwives: specialists in childbirth and women’s health

- Herbalists: deep plant knowledge

- Ritual specialists: when illness crossed into spiritual imbalance

Common illnesses & causes of death

- Infections: wounds, respiratory illness

- Digestive issues: parasites, contaminated water

- Work injuries: farming, carrying heavy loads

- Childbirth: risky, but midwives reduced mortality

- Violence: warfare, punishment, accidents

Family, Kinship & Social Order

Who lived together, and who held the power?

If you want to understand life in 1300 Mexico, forget the modern idea of the isolated nuclear family. Society was built on kin networks, layered, interdependent, and constantly present. You did not grow up alone. You grew up surrounded.

Households: who lived with whom

Most people lived in extended family clusters, not single detached units.

Households typically included:

- parents and children

- grandparents

- sometimes unmarried siblings or widowed relatives

Homes were grouped closely, often around shared patios or courtyards. This was not one giant commune, but it was not “everyone do your own thing” either. Privacy existed, but belonging came first.

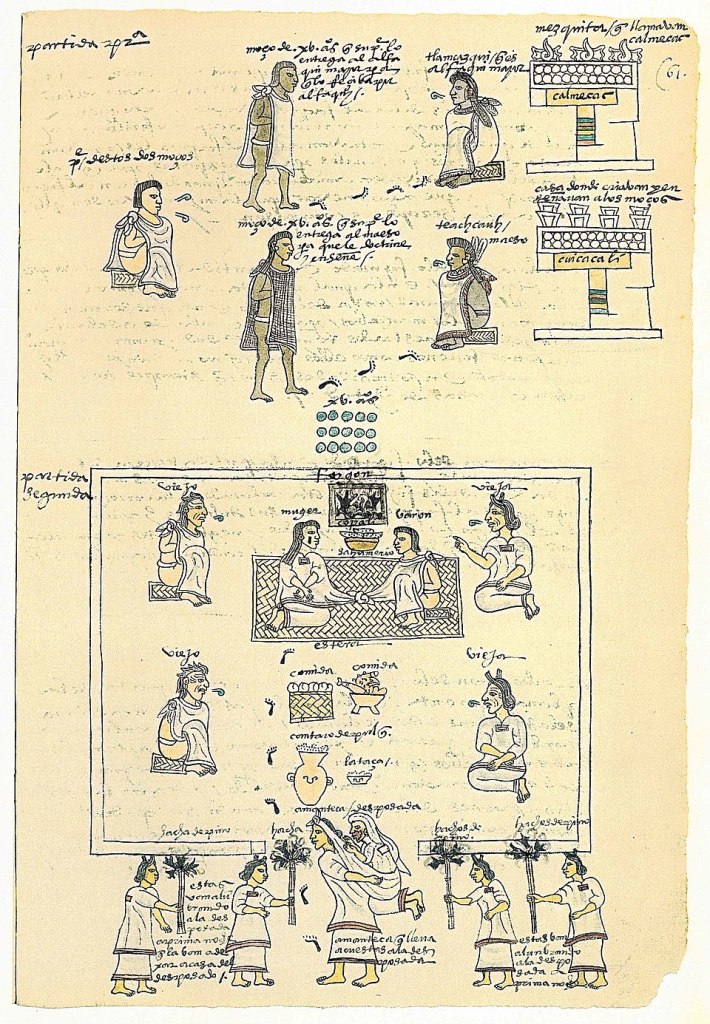

Marriage: how it worked

Marriage was not casual, spontaneous, or private. It was a communal project. Marriage was monogamous for most people. Elites sometimes had multiple wives for political reasons.

According to depictions in the Codex Mendoza and descriptions in the Florentine Codex, Mexica marriage began with planning, negotiation, and ritual timing. The groom’s family initiated the process through a matchmaker, who approached the bride’s family to open talks.

Soothsayers were consulted. The marriage had to fall under a favorable day sign such as Reed, Monkey, Crocodile, Eagle, or House. You did not gamble with a household’s future.

The wedding ritual

The ceremony began after dark. The bride was escorted to the groom’s household in a torch-lit procession, carried on the back of the matchmaker who made the marriage possible.

A large feast followed. Maize was ground in huge quantities. Tamales were piled high. A tripod bowl held turkey, often shown as the head and drumstick. Abundance was displayed openly.

Pulque flowed freely among elders, its foamy surface visible even in the codex imagery.

At the center of the household, copal incense burned at the hearth in honor of Xiuhtecuhtli, the fire god.

Binding a household

Elders surrounded the couple, offering instruction and advice. The bride and groom sat together on a woven mat for the first time. The groom was typically older, usually in his early twenties, expected to complete his training and education before marriage. You did not form a household until you could carry one.

The bride was usually in her late teens. Marriage marked the moment when both were considered capable of contributing fully to family life. Childhood was for training, not drifting, and marriage came only after that preparation was complete.

Gifts were exchanged. The groom’s mother placed a new huipil on the bride. The bride’s mother tied a cape around the groom and laid his loincloth before him. These garments symbolized new roles and responsibilities.

Finally, the matchmakers tied the bride’s huipil and the groom’s cape together. Literally. Visibly. This was the binding act. Afterward, the couple entered seclusion for four days.

Adultery

Adultery was not treated as a private relationship issue. It was treated as a threat to social stability.

Violating it was seen as deception and disorder, not just betrayal.

What counted as adultery

Definitions were strict and gendered.

- married women having sex outside marriage counted as adultery

- married men having sex with married women counted as adultery

- married men with unmarried women or prostitutes usually did not

Punishment and enforcement

According to Indigenous legal traditions later recorded in sources like the Florentine Codex, adultery could be punished by execution, often by stoning, or by severe public punishment leading to death. In some cases, enslavement followed.

These laws were enforced. They were not theoretical. The severity was intentional. In a world without DNA testing, modern courts, or welfare systems, marriage fidelity protected children, inheritance, and survival.

Brutal? Yes. Random? No.

Legally, both parties could be punished. Socially, women bore greater risk.

A woman’s sexual behavior affected lineage certainty, household honor, and her children’s status. Because the system placed more structural weight on women, enforcement often fell harder on them.

This was not about morality. It was about social engineering.

Childhood & Parenthood

What was it like to be a kid or raise one?

Raising children in 1300 Mexico wasn’t about hovering or self-expression. It was about preparing someone to belong. Childhood was short, purposeful, and very social. Kids weren’t the center of the universe, but they were never ignored either.

Parenting style

Think authoritative, not permissive and not cold. Parents expected obedience, but they also showed how to live.

- Mothers: daily care, food, early moral training

- Fathers: work skills, discipline, public behavior

- Grandparents: memory, stories, correction, backup

Affection existed. Hugging, joking, pride, but it wasn’t the point. Competence was love.

Children were trusted with real responsibility early, and that trust shaped them. When you expect competence, you often get it. expectations, not negotiate them. And honestly? They usually did.

Education and training

Education was not optional, but it was not equal. Every child was trained for adulthood, just not for the same future.

Elite boys

Boys born into noble families were prepared for leadership early. Many were sent away from home between 10-13 to live and study in formal institutions.

Their education focused on:

- governance and law

- rhetoric and formal speech

- history and lineage

- moral philosophy

- ritual knowledge

Discipline was intense. Fasting, long hours, and public correction were common. Comfort was not the point. Character was.

Common children

Most children never left home for school, because life itself was the classroom.

Commoner children learned within their households or local training institutions. Their education focused on:

- farming, crafts, and trades

- physical endurance

- cooperation and obedience

- community responsibility

- preparation for labor, marriage, and, for boys, military service

Learning was hands-on and constant. Children watched, copied, failed safely, and tried again. By adolescence, they were already meaningful contributors.

Being a Child in 1300 Mexico

Pros

- Clear expectations, no guessing your role

- Constant community presence

- Early skill-building (confidence comes early)

- Strong sense of belonging

- Time outdoors, moving, exploring

Cons

- Less personal freedom

- Early responsibility

- Harsh discipline by modern standards

- Limited choice in life path

- High risk in early childhood

Being a Parent in 1300 Mexico

Pros

- Community support in raising kids

- Children contributed meaningfully

- Clear cultural scripts for parenting

- Elders offered guidance

- Shared values reduced anxiety

Cons

- Child mortality was emotionally brutal

- Constant labor demands

- Few breaks from caregiving

- Social judgment if kids misbehaved

- Pressure to prepare children early

Pets

Yes… but not “pets” the way we think of them.

- Dogs: common, multifunctional (companionship, protection)

- Turkeys: semi-domesticated, familiar to children

- Birds: occasionally kept, especially colorful species

Animals were part of life, not accessories. Kids learned responsibility early by caring for them.

Leisure, Play & Celebration

How did people have fun when survival already took so much energy?

Leisure in 1300 Mexico was not about escaping life. It was about rebalancing it. Joy lived inside movement, ritual, music, and community. People did not disappear into entertainment. They shared it, loudly and together.

Adults

Music, dance & communal joy

Dance wasn’t optional background fun, it was cultural glue.

- Group dances tied to festivals and seasons

- Drumming, flutes, rattles, chanting

- Rehearsed movements, not freestyle chaos

These dances could go on for hours. Participation mattered more than talent. Sitting out without reason? Kinda weird.

Games, gambling, and play

Patolli (the big one)

The most famous game was patolli. This was the most popular board game in Central Mexico, and it was serious.

- A cross-shaped board marked on mats or stone

- Beans or stones used as dice

- Players wagered valuables: cloaks, cacao, jewelry, even status

- Games could last hours

Patolli was high-stakes gambling with spiritual weight. Losing too much could ruin a person socially. There are accounts of people selling themselves into slavery to cover accumulated gambling debt. Winning brought prestige and envy.

Other adult games included dice-style seed games, athletic contests, mock combat, and competitive dance or endurance performances.

Sports & spectacle

The Mesoamerican ballgame (ōllamalīztli)was not casual recreation.

It was ritualized, competitive, and symbolic. Large crowds gathered to watch. Outcomes could carry political or spiritual weight.

This was adrenaline, identity, and meaning wrapped together.

Markets as social life

Markets weren’t just for shopping, they were social hubs.

People gossiped, flirted, shared news, watched performers, and ate street food. Vendors called out to passersby. Chance encounters were constant.

Festivals and public celebrations

This is where adult leisure went fully public.

Agricultural festivals, religious feast days, market celebrations, and civic or military ceremonies structured the calendar. These were loud, colorful, exhausting days.

People dressed better, ate better, and danced longer. Time was marked not only by work, but by celebration.

Children & Families

Children were rarely separated from daily life, but they had their own forms of play and pleasure.

Children’s play

Children played constantly, though not in isolated “playtime” blocks.

They ran, chased, threw balls, and played imitation games based on adult activities like markets, farming, and household work. Play blended naturally with learning and observation.

Toys

Toys were simple, durable, and effective.

Children played with clay figurines, small dolls, rattles, whistles, and spinning or rolling toys. Most were handmade or repurposed.

Family leisure

Families relaxed together, usually quietly.

After meals, people sat together, listened to elders tell stories, or watched skilled artisans work. Children played nearby, not elsewhere.

Togetherness did not require planning. It was the default state.

Culture, Language & the Sacred World

Explore the worldview, values, and art that shaped daily life.

To live in Mexico in 1300 was to live inside a meaning-saturated world. Nothing was neutral. Time had weight. Words mattered. Art instructed. Religion was not a side activity. It was the operating system.

This wasn’t one culture or one language. It was a mosaic, dozens of peoples, cities, dialects, and traditions layered over shared ideas: maize as sacred, balance as moral, reciprocity as survival.

The Three Major Cultural Powers (and why they mattered)

Mexica (Aztec)

Quick Sidebar: “Aztec” vs. “Mexica”

The people we usually call “Aztecs” didn’t use that name for themselves. They called themselves Mexica.

The word Aztec comes from Aztlán, the legendary homeland the Mexica said their ancestors migrated from. Spanish chroniclers later used Azteca as a catch-all label of basically, “the people who came from Aztlán.” It stuck in European writing, even though it wasn’t how the people identified themselves.

So when you see Aztec, think Mexica: the name they actually lived with, ruled under, and spoke aloud.

Why they mattered: organization, scale, ambition

The Mexica were the political and military powerhouse of Central Mexico. They excelled at coordination. Cities, markets, tribute systems, and ritual calendars all worked together.

They were not the most ancient culture, but they were highly effective. Their strength was control of people, food, belief, and time.

Maya

Why they mattered: knowledge, writing, time

The Maya developed advanced astronomy, mathematics, and fully developed writing systems. Their cities were planned around water, ritual, and calendar cycles.

By 1300, political power had shifted, but cultural and intellectual traditions remained strong. Sacred knowledge does not vanish just because capitals move.

Mixtec

Why they mattered: art, history, lineage

The Mixtec were renowned for metalwork, jewelry, and painted manuscripts. Their codices preserved genealogy and political memory across generations.

If the Mexica ruled with power and the Maya with knowledge, the Mixtec ruled with memory.

Religious & spiritual life (woven into everything)

Religion was not about faith alone. It was about keeping the world working.

The gods were forces of nature, time, fertility, and death. They were cyclical, demanding, and hungry.

Core ideas included:

- balance rather than good versus evil

- reciprocity rather than worship

- humility before cosmic forces

The world required care. Ritual was how that care was performed.

- Gods: forces of nature, time, fertility, death

- Rituals: offerings, fasting, dance, bloodletting

- Calendars: sacred timekeeping guided decisions

- Moral code: balance, reciprocity, humility before the cosmos

Sacrifice and cosmic debt

Yes, sacrifice happened. And yes, it was real.

At the center of Mexica religion was not cruelty. It was cosmology.

The Mexica believed life existed only because the gods had already sacrificed themselves. In their creation stories, gods threw themselves into fire to bring the sun into being. They shed divine blood to form humanity. Creation was paid for in pain and loss.

That belief produced a moral logic. Life runs on debt.

If the gods gave their bodies so the world could move, humans were obligated to return something. This was not optional devotion. It was reciprocity.

What that debt required

The Mexica are perhaps most famous for human sacrifice, and yes, also for the spectacle around it. Prisoners of war were sacrificed, but so were select members of their own society who were chosen to embody specific gods for a full year before dying in a public ritual. At the center of this practice was a covenant called tlatlatlaqualiliztli, meaning “the nourishment of the gods with the blood of sacrifice.”

The logic was direct and uncompromising. Life existed because the gods had already given everything, and blood was the only substance worthy of repayment. In its most extreme form, this covenant culminated in human sacrifice, including the offering of still-beating hearts to the gods.

Those chosen to impersonate deities entered the role knowingly and voluntarily as it was a high honor. By giving their blood, they were not being punished. They were returning the gift of life that the gods had given them at birth.

Children were sometimes sacrificed to the rain god Tlaloc, particularly on sacred mountains. Their tears were believed to call rain. This was not seen as cruelty. It was seen as necessity within a cosmology where survival depended on cosmic balance.

What sacrifice meant

To honor the debt the gods had paid, the Mexica built major temples that served as sites of exchange between humans and gods.

Rituals included:

- bloodletting

- auto-sacrifice (offering one’s own blood)

- human sacrifice

These were not everyday acts. They were the highest expressions of obligation. Blood mattered because blood was life itself.

Offering human blood was not about death for its own sake. It was about feeding the sun, sustaining rain, and preventing collapse.

Within this worldview, sacrifice was ethical. It was responsibility.

Art as instruction

Art was not decoration. It taught people how to see the world.

Common forms included stone sculpture, murals, codices, and textiles. Style was symbolic, bold, and rhythmic.

Color carried meaning:

- Red signaled life force, blood, sunrise, and renewal

- Blue/turquoise marked water, sky, rain, and sacred power

- Black represented night, death, earth, and hidden forces

- White marked completion, bones, age, and transition

Artists were respected specialists, often anonymous. Art was not about originality. It was about correct repetition. Doing it the right way mattered more than doing it your way.

Language, speech, and record

Mexico in 1300 was deeply multilingual.

Languages included Nahuatl, multiple Maya languages, Mixteco, Zapoteco, and Otomí. Dialects were regional and fluid.

Literacy was specialized. Scribes, priests, and elites recorded history, ritual, and lineage through pictographic and glyph-based systems.

Writing was not for everyday notes. It was for power, memory, and time. Oral tradition carried the rest.

Music & Instruments

What did it sound like?

If you walked through Mexico in 1300, silence would feel wrong. Music was signal, prayer, memory, and movement. It marked time — work starting, ritual beginning, danger approaching, celebration peaking. You didn’t “put music on.” You entered it.

Instruments: the sound palette

No strings yet. This world leaned on breath, skin, wood, and stone.

- Drums:

- Huehuetl (vertical log drum, deep heartbeat)

- Teponaztli (horizontal slit drum, melodic rhythm)

- Wind instruments:

- Clay ocarinas, flutes, whistles (some animal-shaped)

- Bone and reed flutes with sharp, piercing tones

- Rattles & shakers:

- Gourd rattles, seed pods, shells

- Shell trumpets:

- Loud, ceremonial, used for calls and announcements

Textures mattered. Rough wood, stretched hide, cool clay. Sound came from the earth, literally.

How music was used

Music wasn’t background, it was functional.

- Ritual: ceremonies, offerings, calendrical feasts

- Dance: synchronized movement, community cohesion

- War & state: signals, intimidation, morale

- Work & teaching: rhythm for labor, memory aids

Musicians trained for years. Getting a rhythm wrong during ritual wasn’t “oops”, it was cosmically awkward.

“Playlist” modern recordings that get us close

We don’t have original recordings (obvio), but we do have careful reconstructions using period instruments and sources. If you want to feel 1300-ish sound, start here:

- Xochipilli – Carlos Del Río: deep percussion and breathy winds

- Teponaztli – Nahuales Negros: pure rhythmic structure

- Mayan Fire Flute – Xavier Quijas Yxayotl: sharp, airy, haunting

Media You Can Watch or Read Today

Continue your journey with these books and movies.

Adults

If you want to understand Mexico around 1300, not just the dates but the mindset, rhythm, and stakes, these are the works I point people to. Some are intense. Some are poetic. Some are imperfect but invaluable. Together, they help you feel the world, not just learn about it.

Movies & TV

- Apocalypto (2006)

Language: Yucatec Maya (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: English subtitles widely available

A brutal, kinetic survival story set in the late Postclassic Maya world. Violent and controversial, but visually immersive. You feel the jungle, ritual life, fear, and social pressure of a society under strain. Not a documentary, but it feels like a world with rules. - Retorno a Aztlán (1990)

Language: Nahuatl (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish subtitles (availability varies)

A deep-cut gem. Mythic, symbolic, and unapologetically Indigenous in structure. This film explores Mexica cosmology, memory, and identity without translating itself for Western storytelling expectations. Slow, reflective, and powerful if you’re ready to sit with it.

Books & Reading

- Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs

Language: English

It tells Mexica history through Indigenous voices and Nahua sources rather than colonial framing. Clear, humane, and quietly radical. You finish it understanding why life in 1300 made sense to the people living it. - Popol Vuh

Language: Originally K’iche’ Maya

Translated: English & Spanish editions available

This is myth, not straight history, but it’s foundational. Creation stories, gods, cosmic cycles, moral logic. If you want to understand how people thought about time, sacrifice, and balance, this text is essential. Read slowly. Let it be strange. - Aztec – Gary Jennings

Language: English

An epic historical novel following a fictional Mexica man who survives the Spanish conquest and reflects back on his life as a warrior, scribe, merchant, and court insider. The story is long, messy, and vivid, full of markets, travel, ritual, humor, ambition, and brutality. Not perfect, but deeply immersive, it’s one of the most textured fictional portrayals of pre-contact Mexica life available - The Broken Spears

Language: Spanish (original)

Translated: English available

This edges into the conquest period, but it belongs here. It preserves Indigenous voices looking back at the world that existed before everything broke. Reading it after learning about 1300 hits harder, you understand what was actually lost.

Kids

Movies & TV

- Las Leyendas

Language: Spanish (original); Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 8–12

Okay, this is my go-to recommendation. It’s spooky but not nightmare fuel, funny without being dumb, and deeply rooted in Mexican folklore and pre-Hispanic monsters. It doesn’t lecture, it just normalizes Indigenous mythology as part of everyday Mexican life. Great for kids who like mystery and adventure. - La Leyenda de la Nahuala

Language: Spanish (original); Dubbed/Subtitled: English available in some releases

Ages: 7–11

This one feels like telling a ghost story at a family gathering. It’s set later historically, but the monster lore, worldview, and moral logic are straight out of Indigenous tradition. Sweet, funny, and a little spooky, perfect if your kid likes courage stories without constant peril. - Maya and the Three

Language: English (original); Dubbed: Spanish available

Ages: 8–12

This is fantasy, yes, but it’s clearly inspired by Mesoamerican cultures, gods, aesthetics, and values. Strong female lead, epic quest energy, and a visual style that opens the door to conversations about ancient Mexico without needing a history lesson mid-episode.

Books

- La creación del Sol y la Luna

Language: Spanish (original); Translated: Some bilingual editions available

Ages: 6–10

Short, beautiful, and meaningful. This one explains a key Mexica creation story in a way that kids get. It’s perfect if you want something calm, reflective, and culturally grounded, especially for bedtime reading. - The Corn Grows Ripe

Language: English (original)

Ages: 9–12

This is quieter, slower, and very grounded. It follows a Maya boy growing up, learning responsibility, and finding his place in his community. No fantasy, no action scenes — just daily life. Ideal for thoughtful kids who like realistic stories and cultural immersion.

So… would you thrive in Mexico around 1300 AD — waking with the sun, eating what the land provided, living shoulder-to-shoulder with family and community — or would you struggle without plumbing, podcasts, and late-night snacks on demand? However you answer, one thing is clear: this world wasn’t primitive or empty. It was full, functional, and deeply human. Leave your thoughts below or tag me on social — I’d love to know where you think you’d land.

Leave a comment