Step into a different time. In this post, we’re walking through everyday life in 900 AD Mexico: how people lived, worked, ate, raised families, and made meaning from sunrise to nightfall.

Just so we’re all on the same page. Please ensure you’ve made yourself acquainted with my disclaimer

Home Life

Step into a house in Mexico around 900 AD and you’ll notice it right away: one shared space, simple materials, and a daily rhythm shaped entirely by daylight. This is where people slept, cooked, cleaned, worked, and talked. Life layered on top of itself, no walls needed. Private rooms weren’t the goal; community and practicality were.

What a Typical House Looked Like

Most households were single-story structures built with adobe (mudbrick) or wattle-and-daub, packed tight and cool to the touch. Floors were hard-packed earth; walls were matte, sandy, sometimes washed with lime so they glowed softly in the sun.

- Size: roughly 25–40 m² (270–430 sq ft)

- Rooms: usually one main multipurpose room, sometimes with a small storage nook

- Bedrooms/Bathrooms: none, at least not how we think of them

Sleeping, Rest, and the Rhythm of the Day

Sleep followed the sun, no alarms, no blackout curtains. Nights were dark-dark, so people slept earlier and woke before sunrise, especially in farming communities.

- Beds: woven reed mats (petates) laid directly on the floor

- Bedding: cotton blankets or cloaks, slightly rough, smelling of earth and smoke

- Who slept where: families slept together, space rearranged nightly

- Naps: sí, especially midday during heat or after heavy work

Cleanliness & Daily Hygiene

No bathrooms, no plumbing, but don’t confuse that with “dirty.” Cleanliness was practical and ritual at the same time.

- Bathing: washing with water carried in clay vessels; rivers and temazcales nearby

- Soap: plant-based cleansers, ashes, or herbal infusions

- Toileting: outdoors, away from living spaces

- Laundry: hand-washed, sun-dried, stiff but fresh

Culturally Important Objects in the Home

A house wasn’t complete without its tools and sacred corners. These objects weren’t decor, they were life.

- Metate & mano: stone grinding slab and handstone

- Comal: flat clay griddle, blackened from years of tortillas

- Clay ollas: round-bellied pots for water, maize, stews

- Storage baskets: woven fiber

- Shrine space: small and simple, with offerings of food, flowers, obsidian, or figurines

Fashion & Beauty Standards

What did people wear, how did they groom themselves, and what did “looking good” mean in daily life?

Everyday Clothing: Materials & Silhouettes

Clothing in 900 AD Mexico was functional, breathable, and made to last. Most garments were woven from cotton in warmer regions or maguey (agave) fiber elsewhere, usually left undyed or colored with mineral and plant dyes.

- Core garments (with regional variation):

- Maxtlatl: loincloth worn by men

- Huipil: sleeveless or short-sleeved tunic worn by women

- Tilmatli: cloak or wrap for warmth, travel, or status

- Wrap skirts: women typically paired huipiles with wrapped skirts (cueitl/enredo-style)

- As a random aside: separate “underwear” as we imagine it today was uncommon or absent

- Silhouettes: straight, loose, and draped (not fitted)

- Fastenings: tied with woven belts or cords; no buttons or metal closures

These clothes were made for walking long distances, squatting at work, carrying loads, and living in heat.

Accessories & Visible Adornment

Adornment signaled identity, region, and social standing more than personal taste.

- Jewelry: jade, shell, obsidian, bone, copper

- Earspools & piercings: common, especially among elites

- Necklaces & pendants: often symbolic or protective

- Textiles as status: finer weaves and brighter dyes marked higher rank

- Headbands or wraps: mostly practical, sometimes decorative

Hair, Grooming & Daily Appearance

Hair was kept intentional and maintained (this wasn’t a messy society).

- Hairstyles: long hair worn loose, braided, or tied back

- Facial hair: generally minimal or absent

- Due to genetics, most men could not grow full beards. Sparse facial hair was often trimmed or removed

- Grooming tools: obsidian blades, stone tools, natural oils

- Cleanliness: regular washing using water, herbs, and steam baths

- Average height:

- Men: about 153–157 cm (5’0”–5’2”)

- Women: about 140–145 cm (4’7”–4’9”)

Cosmetics, Body Art & Modification

Body modification existed, but it followed cultural rules, not personal experimentation.

- Body paint: mineral or plant pigments for ritual or ceremony

- Tattoos: present but not universal; meanings varied by group

- Piercings & scarification: culturally specific, often symbolic

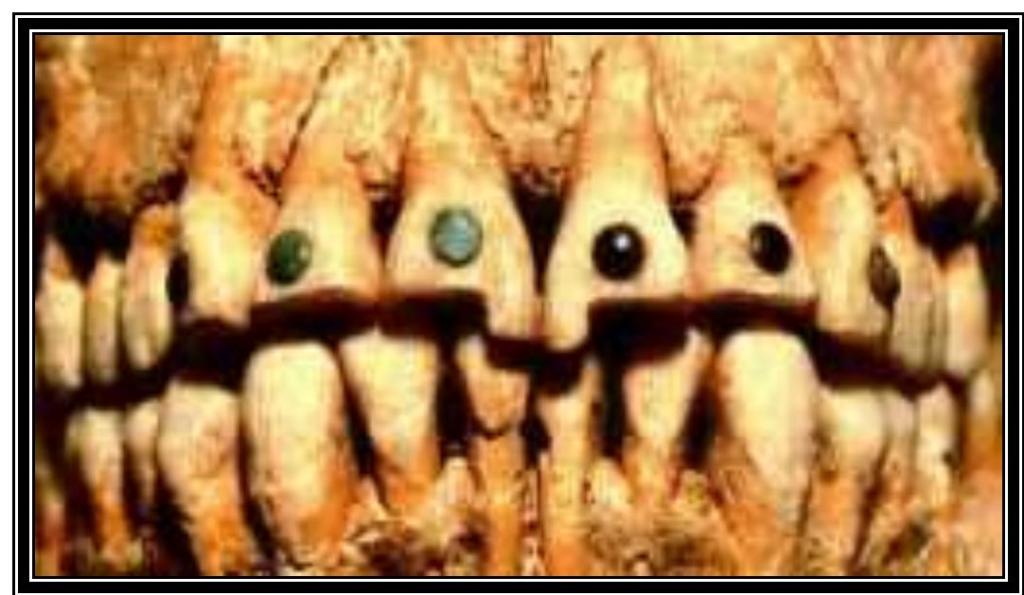

- Teeth inlays: jade or stone among elites

- Cranial modification:

- Infants’ skulls were gently shaped using boards or bindings

- A flattened or elongated head could signal identity and (often) higher status

- Cranial modification was widespread but selective. It depended on region, culture, and family identity, not just wealth.

- Some groups never practiced it, and even within the same city, styles and prevalence varied.

Diet & Daily Meals

What they grew, gathered, cooked, and relied on to get through the day.

Food wasn’t entertainment or indulgence, it was survival, balance, and responsibility. Eating meant maintaining harmony between people, land, seasons, and spirits. You didn’t ask “what do I feel like today?” You ate what the milpa and the moment allowed.

Meals were communal, routine, and deeply practical. Food was nourishment first, meaning second, pleasure third.

Staple Foods: The Daily Foundation

The diet was built around crops that worked together, nutritionally and agriculturally.

- Maize: eaten daily as tortillas, tamales, atole, or gruel

- Beans: regional varieties for protein

- Squash: flesh, seeds, and blossoms (nothing wasted)

- Chiles: fresh or dried, mild to fiery

- Amaranth: grains and greens

- Wild greens: quelites, herbs, leafy plants

- Occasional proteins: turkey, insects, fish, small game, and dog in some regions

Daily Drinks

Most hydration came from simple, functional drinks.

- Water: carried and stored in clay ollas

- Atole: warm maize drink, thick and filling

- Cacao drinks: bitter, spiced, and mostly ritual or elite

- Fermented beverages: pulque in some regions

How Much Time Food Took

Food didn’t magically appear; it shaped the entire day.

- Farming: dawn to late morning during planting and harvest seasons

- Foraging: ongoing activity; greens, insects, fruits gathered as needed

- Hunting & fishing: supplemental, not constant

- Food prep: hours daily, especially grinding maize on the metate

- Trading: local markets filled gaps the household couldn’t produce, if someone was sick, had just given birth, or harvest demanded every hand, you could trade instead of grind maize that day.

Meals, Timing & Routine

People didn’t follow modern meal structures. Eating happened when it made sense.

- Morning: leftover tortillas, atole, or maize gruel

- Midday: portable foods eaten near fields or work areas

- Evening: the main communal meal, cooked fresh and shared

No snacks, no grazing culture, just steady fuel. Not to say snacks NEVER happened, sampling berries while foraging? Obviously. But food wasn’t eaten casually.

OG Meal

Food was prepared over open hearths using clay comales and ollas. Meals followed labor rhythms, not clock time. Tortillas doubled as food and utensil.

- Morning

- Warm maize atole: Lightly thickened, unsweetened. Sometimes faintly seasoned with chile

- Midday

- Toasted pumpkin seeds (pepitas): Dry-toasted on a comal

- Main Communal Meal. Foods were eaten together, not as courses

- Sweet:

- Pumpkin & honey ceremonial tamal (Quick note: Sweetness in 900 AD Mexico came from rarity, not sugar. A squash-filled tamal lightly touched with honey would have been an exceptional food, reserved for ritual moments rather than daily life.)

- Drink: Cacao beverage (same here, cacao was for elite or ceremonial contexts only)

Modern Meal

The flavors endure, even if the kitchen has changed.

- Breakfast:

- Corn porridge with roasted chile oil: Stone-ground corn grits simmered with water. Drizzled with chile-infused oil and sea salt

- Snack:

- Pepita with smoked chile and salt: Toasted pumpkin seeds, coated with smoked chile, flaky salt, citrus zest

- Dinner:

- Deconstructed tamal bowl: Whipped masa base, slow-simmered beans, roasted squash and seasonal greens, drizzled with a chili sauce.

- Drink: Still water or lightly fermented maize beverage

- Dessert:

- Pumpkin pie tamal: Steamed corn cake with a warm spiced pumpkin purée folded in, a honey drizzle along with candied pepita crumble

- Drink: Cacao latte

Climate & Environment

Where people lived shaped how they worked, dressed, ate, and survived, every single day.

1. Northern Arid Lands (Chihuahua & Sonoran regions)

This was dry country. Wide skies, sharp light, and long distances between water.

- Summer: ~32–40 °C (90–104 °F), humidity ~15–25%

- Winter: ~5–15 °C (41–59 °F), humidity ~20–30%

- What it feels like: hot sun that dries your skin fast; shade matters more than breeze

- Landscape: desert plains, scrub, rocky hills, sparse grasses

2. Central Mexican Highlands (Valley of Mexico)

High elevation meant milder temperatures and predictable seasons, prime farming land.

- Summer: ~22–26 °C (72–79 °F), humidity ~40–55%

- Winter: ~5–15 °C (41–59 °F), humidity ~30–45%

- What it feels like: warm days, cool nights; you want a cloak after sunset

- Landscape: high plateaus, lakes, volcanic soil, rolling fields

3. Gulf Coast Lowlands (Veracruz region)

Hot, humid, green, and alive. The air itself felt heavy.

- Summer: ~30–34 °C (86–93 °F), humidity ~75–90%

- Winter: ~18–24 °C (64–75 °F), humidity ~65–80%

- What it feels like: sweaty the moment you stop moving; clothes cling

- Landscape: tropical forests, wetlands, rivers, coastal plains

4. Southern Highlands (Oaxaca region)

Cooler air, steep terrain, and intense microclimates that shifted with elevation.

- Summer: ~20–25 °C (68–77 °F), humidity ~50–65%

- Winter: ~8–18 °C (46–64 °F), humidity ~40–55%

- What it feels like: crisp mornings, warm sun, cool shade

- Landscape: forested mountains, valleys, terraces

5. Maya Lowlands (Yucatán Peninsula)

Flat, hot, and seasonally extreme, water controlled everything.

- Summer: ~30–35 °C (86–95 °F), humidity ~70–85%

- Winter: ~20–25 °C (68–77 °F), humidity ~60–70%

- What it feels like: thick heat, especially before rain; shade is survival

- Landscape: limestone plains, cenotes, tropical forest

Population & Major Cities

Where people lived, how dense those places were, and why certain cities mattered so much.

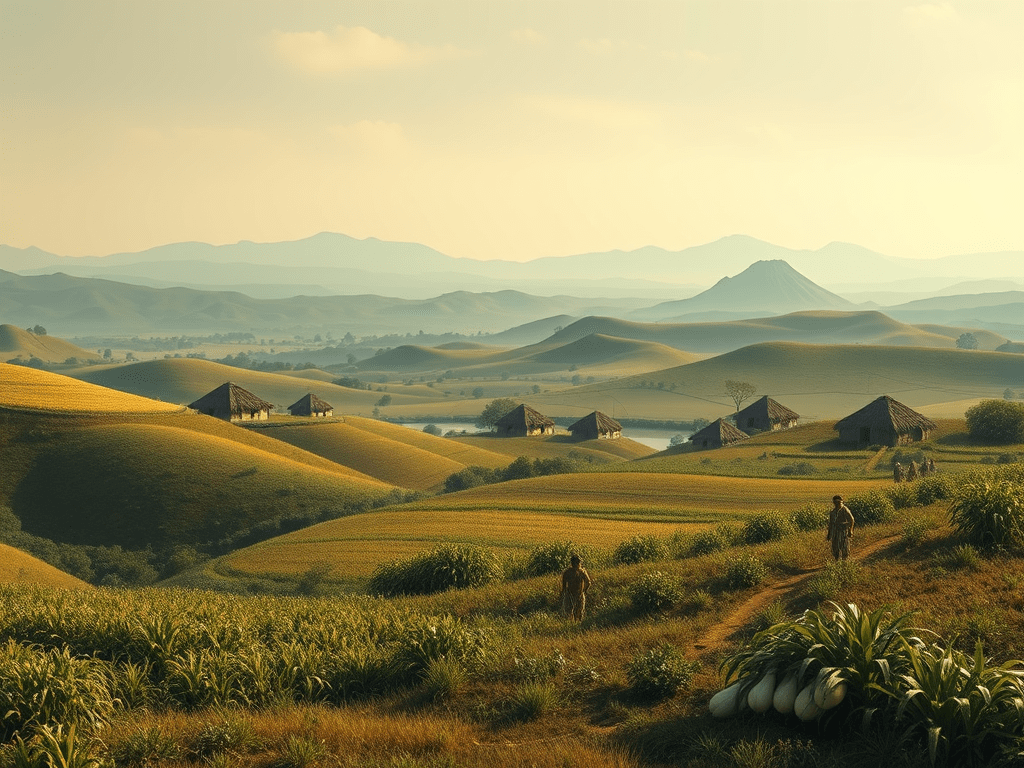

By 900 AD, much of Mexico was densely settled, not everywhere, but in the right places. Valleys, coasts, and trade corridors filled up fast.

- Estimated population: roughly 10–15 million people across what is now Mexico

- Settlement pattern:

- Large cities surrounded by villages and farmsteads

- Rural populations feeding urban centers

- Density: some regions rivaled or exceeded parts of medieval Europe

This wasn’t an empty land waiting to be filled. It was already busy.

The Top Cities (by Influence & Population)

1. Tula (Tollan) – Central Mexico

Towering stone figures standing guard where Toltec power, ritual, and muscle memory met. These weren’t decorative statues; they were architecture doing propaganda.

By 900 AD, Tula was on the rise, becoming a major political and military center associated with the Toltecs.

- Estimated population: ~30,000–40,000

- Why it mattered:

- Power base for Toltec influence

- Military prestige and long-distance trade

- Architectural style that spread far beyond the city

2. Chichén Itzá – Northern Yucatán

Ceremonial architecture built to anchor ritual life and seasonal timekeeping

A true heavyweight of the Maya world during this period.

- Estimated population: ~35,000–50,000

- Why it mattered:

- Political, religious, and trade hub

- Control of routes linking inland Yucatán to the coast

- Cultural blending of Maya and central Mexican influences

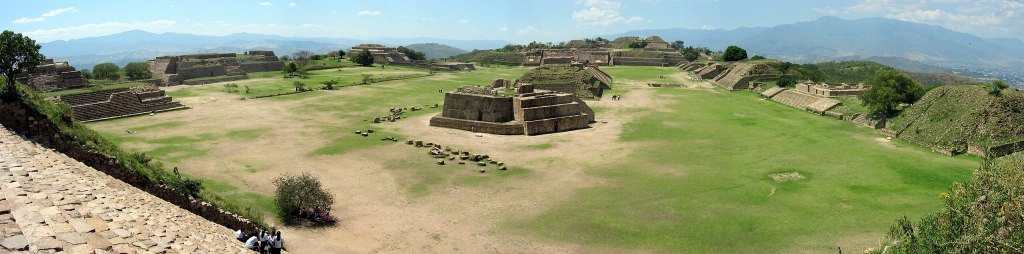

3. Monte Albán – Oaxaca Valley

A long-standing ceremonial and political center, positioned to oversee surrounding valleys and reinforce authority through scale, placement, and ritual use.

Older than the others, but still symbolically powerful around 900 AD, even as its population declined.

- Estimated population: ~25,000–30,000

- Status by 900 AD: reduced population, enduring influence

- Why it mattered:

- Early urban planning and writing systems

- Long-standing political memory for the region

4. El Tajín – Gulf Coast (Veracruz)

A ceremonial structure defined by repetition and precision, where architecture, calendrical meaning, and public ritual were built directly into the façade. Photo: Arian Zwegers / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0

A vibrant city in a hot, humid environment, and it thrived there.

- Estimated population: ~15,000–20,000

- Why it mattered:

- Major cultural and ceremonial center

- Distinct architectural style

- Deep connection to ballgame traditions

5. Xochicalco – Morelos Highlands

A carved ceremonial structure linking rulership, calendrical knowledge, and shared religious symbols across regions.

Smaller, but strategically placed, and that made all the difference.

- Estimated population: ~10,000–15,000

- Why it mattered:

- Trade crossroads

- Astronomical knowledge and calendrical power

- Cultural exchange hub after Teotihuacán’s collapse

Economy & Work

How people survived, traded, and understood value, without coins, paychecks, or a “middle class.”

Was There Money?

Short answer: not really, at least not the way we think of it.

Around 900 AD, most of Mexico ran on barter, tribute, and obligation, not coins. Some items functioned like proto-currency, but they weren’t universal or standardized.

- Primary system: barter and reciprocal exchange

- Supplemental system: tribute paid to elites or city authorities

- Markets: yes, but prices were flexible and situational. Value was negotiated, not printed.

What People Traded

Everyday exchange focused on necessities and skilled labor.

- Staple foods: maize, beans, chile, squash

- Craft goods: pottery, woven textiles, tools

- Luxury items: cacao beans, jade, obsidian, feathers

- Services: labor, transport, food preparation, craftwork

Class Structure: Who Had More, Who Had Less

Society was clearly stratified, even without money.

- Elites: rulers, nobles, high-ranking priests

- Skilled specialists: artisans, traders, scribes

- Commoners: farmers, laborers, fishers

- Dependents: servants, captives, enslaved individuals

Could People Move Up or Down?

Yes, but slowly, and not equally.

- Upward movement: through skill, trade success, religious roles, or political favor

- Downward movement: drought, illness, loss of land, war

- Inheritance mattered, but so did reputation and alliances

Status wasn’t frozen, but it wasn’t fluid either. Most people lived close to where they were born, socially as well as geographically.

Health & Survival

How long people lived, what made them sick, and how they tried to stay alive.

The Big Picture: Health Outlook

Health in 900 AD Mexico was shaped by environment, diet, and luck. There were no antibiotics, no germ theory, but there was deep practical knowledge of the body and the natural world. People paid attention. They observed patterns. They learned what worked.

Life wasn’t fragile in the way people sometimes imagine, but it was unforgiving when things went wrong.

Survival depended on community as much as medicine.

Life Expectancy

This is where numbers can mislead if we don’t explain them.

- If you survived childhood: many people lived into their 40s or 50s

- Elders existed, especially among those with stable food access and lower physical strain

Child Survival

Childhood was the most dangerous stage of life.

- Estimated survival to adulthood: a large proportion died before adulthood in most populations

- Highest risk period: birth to age 5

Once a child made it through those early years, their odds improved significantly.

Medicine & Healing Practices

Healthcare was hands-on, local, and knowledge-based, not primitive, just different.

- Healers: herbal specialists, ritual healers, midwives

- Knowledge source: passed through families and apprenticeships

- Treatments: plant medicines, poultices, steam baths, massage

- Surgery: limited but present (wound care, bone setting)

Practical medicinal knowledge existed across Mesoamerica before European contact, including splinting fractures and treating wounds.

Healing often blended physical care with spiritual balance.

Folk Remedies & Common Treatments

People relied heavily on the plant world and ritual healing.

- Herbs: for pain, infection, digestion, fertility

- Temazcal (steam bath): used for illness, recovery, and childbirth, especially among Maya and other groups

- Other traditional practices: sweating, poultices, plant infusions

Medicine wasn’t standardized, it was adaptive and locally grounded.

Common Causes of Death

Death usually came from everyday risks, not dramatic disease outbreaks.

- Childbirth complications

- Infections

- Malnutrition during drought

- Accidents

- Violence or warfare

Childhood & Parenthood

What it meant to grow up, and what it took to raise the next generation.

Parenthood: The Good and the Hard

Raising children wasn’t a personal lifestyle choice, it was a social obligation. Kids were the future workforce, memory keepers, and spiritual continuity of the community.

Pros of being a parent:

- Extra hands for food production and household work

- Social respect, parenthood marked full adulthood

- Strong family bonds and shared responsibility

- Support in old age

- Continuation of lineage and memory

Cons of being a parent:

- High risk of losing children in early years

- Constant physical and emotional labor

- Food scarcity hit parents hardest

- Mothers faced real danger during childbirth

- Little rest, parenting was full-time, always

Childhood: The Good and the Hard

Being a child meant freedom and responsibility.

Pros of being a child:

- Constant presence of extended family

- Strong sense of belonging

- Clear expectations, you knew your role

- Daily time outdoors

- Learning skills early

Cons of being a child:

- High risk of illness or death

- Expected to work from a young age

- Little personal autonomy

- Physical labor could be demanding

- Few protections if food was scarce

Pets & Animals in the Household

Animals weren’t pets in the modern sense, but they were part of daily life.

- Dogs: common, used for companionship, protection, and sometimes food

- Turkeys: domesticated, especially in central and southern regions

- Other animals: birds or small creatures occasionally kept, often temporarily

Animals had roles. Affection existed, but utility came first.

Cultural Expectations of Children

Children weren’t seen as “in training.” They were already contributing members of society.

- Obedience: expected, especially toward elders

- Labor: age-appropriate tasks from early childhood

- Education: informal; skills, stories, and ritual knowledge

- Gender roles: learned early through daily participation

- Marriageability: social readiness mattered more than romance

By adolescence, children were expected to function almost fully as adults. Growing up meant learning how to belong, not how to stand out.

When Did a Child Become a “Person”?

Among the ancient Maya, children weren’t automatically seen as full social beings at birth. Instead, being a person was something you grew into, spiritually, socially, and ritually.

At birth, a child was considered vulnerable and unfinished. Their soul wasn’t yet fully anchored to their body, which meant early life was a in between stage, not quite divine, not quite human.

- Early rituals: naming ceremonies, water rites, or baptism-like practices helped “tie” the soul to the body

- Purpose: these ceremonies didn’t celebrate birth so much as secure survival and identity

These rituals marked the moment when a baby became recognizable to the community, not just alive, but someone.

Children in the In-Between

Because children weren’t yet fully socialized, they occupied a between-state.

- Spiritually closer to the divine world

- Socially not yet bound by full adult obligations

- Seen as powerful and fragile at the same time

That in between status helps explain something that’s hard for us modern readers to sit with.

In some Maya belief systems, sacrifice wasn’t understood as destruction, but as transformation, a return of life-force back to the gods to sustain cosmic balance. When children appear in ritual sacrifice contexts, it likely reflected ideas of renewal, rebirth, not punishment or cruelty.

Children symbolized new life. And new life carried spiritual weight.

Growing Into Social Life

Ethnographic evidence from later Maya communities helps us glimpse how childhood unfolded day by day.

- Birth to ~3 years:

- Children were nurtured closely

- Allowed to play freely

- Rarely disciplined

- Ages ~3–9:

- Light chores introduced

- Expectations increased gradually

- Later childhood:

- Boys and girls separated into more defined roles

- Work became more physically demanding

Social identity wasn’t assigned all at once. It was layered on over time. To grow up wasn’t just to get older, it was to become fully human, piece by piece.

Leisure & Recreation

Leisure in 900 AD Mexico didn’t mean escaping daily life, it meant pausing within it. Fun was social, physical, and often tied to ritual, markets, or the agricultural calendar.

Adults: How Grown-Ups Spent Their “Free” Time

Rest and joy were folded into community rhythms, not scheduled around them. You didn’t clock out — you joined in.

- Ballgame (ōllamaliztli):

- Played and watched across Mesoamerica

- Part sport, part ritual, sometimes political

- Heavy rubber ball, stone courts, loud crowds

- Music & dance:

- Drums, flutes, rattles

- Group dances during ceremonies and festivals

- Ritual gatherings:

- Religious observances doubled as social events

- Food, music, movement, and shared emotion

- Markets & trade days:

- Busy, noisy, social

- A place to talk, joke, gossip, and exchange news

- Pulque drinking (regionally):

- Fermented maguey drink

- Usually limited to elders, ritual use, or specific occasions

Children & Families: Play, Learning, and Imitation

Children played constantly, often while learning adult roles.

- Imitative play:

- Pretending to grind maize, hunt, cook, or trade

- Physical games:

- Running, chasing, wrestling, ball play

- Simple toys:

- Clay figurines, dolls, small animals

- “Nature Toys” – Think the random things kids pick up on hikes.

- Riddles & storytelling:

- Shared by elders during rest periods or evenings

- Family participation:

- Children attended rituals, markets, and festivals alongside adults

Culture, Language & Religion

How people understood the world, spoke to each other, and made meaning through ritual and art.

Mexico Around 900 AD: The Big Picture

Mexico at this time wasn’t one culture or one belief system. It was a mosaic, dozens of societies linked by trade, shared symbols, and overlapping worldviews, but still fiercely regional.

People understood life as cyclical, relational, and sacred. Mountains, rain, maize, ancestors, all of it mattered. Religion wasn’t a separate category from daily life. It was the operating system.

The Three Major Cultural Spheres

1. Maya (Southern Mexico & Yucatán)

By 900 AD, the Maya world was changing, some Classic cities declining, others adapting, but Maya culture was still deeply influential.

- Known for: writing, calendars, astronomy, ritual architecture

- Worldview: time as cyclical; humans as caretakers of cosmic balance

- Religion: many gods tied to rain, maize, death, and creation

- Social life: ritual calendars structured daily and seasonal life

2. Central Mexican Traditions (Post-Teotihuacán / Early Toltec world)

After Teotihuacán’s collapse, central Mexico reorganized rather than disappeared.

- Known for: militarized power, trade networks, monumental stonework

- Worldview: authority tied to lineage, conquest, and ritual legitimacy

- Religion: gods of rain, war, fire, and fertility

- Social life: public ritual reinforced political power

3. Oaxaca & Southern Highlands (Zapotec-Mixtec traditions)

In Oaxaca, older traditions endured with remarkable continuity.

- Known for: long memory, genealogies, carved stone records

- Worldview: ancestry and land as sources of authority

- Religion: earth, rain, and ancestral spirits

- Social life: elite lineages mattered deeply

Religion & Spiritual Life

Everyone practiced religion. Not as belief alone, but as action.

- Gods: many, often overlapping: rain, maize, sun, death, fertility

- Rituals: offerings, fasting, bloodletting, dance, prayer

- Sacred spaces: temples, caves, mountains, cenotes

- Moral code: balance, obligation, respect for elders and gods

Faith wasn’t optional. It structured time, labor, and social order. You didn’t ask if the gods mattered, you asked how to stay in balance with them.

Art & Aesthetic Values

- Media: stone carving, mural painting, ceramics, textiles, featherwork

- Subjects: gods, rulers, ancestors, mythic scenes

- Purpose: ritual memory, political legitimacy, cosmic order

Language, Speech & Writing

Mexico was — and is — multilingual

- Spoken languages: Maya languages, Zapotec, Mixtec, Nahuatl (early forms), and many others

- Dialects: varied by region, city, and even neighborhood

- Writing systems:

- Maya: fully developed hieroglyphic writing

- Others: pictorial or mnemonic systems

- Literacy: limited to specialists, scribes, priests, elites

Most people learned through listening, watching, and doing, not reading.

Historical Catch-Up

What changed, what endured, and what shaped life between 600 and 900 AD.

What Happened to Teotihuacán?

Earlier, you may have noticed a major absence.

In 600 AD Teotihuacán was still one of the most powerful cities in the Americas, massive, organized, and influential. But by 900 AD? Its days as a megacity were over. The pyramids were still standing, but the city itself was pretty much abandoned.

The Collapse

In 650 AD archaeology shows clear signs that something went very wrong.

- Elite compounds were burned deliberately, not randomly

- Public buildings show damage and abandonment

- The political system that held the city together fractured

This wasn’t a natural disaster wiping everyone out. It looks more like internal unrest, possibly combined with drought, resource strain, and social inequality.

Teotihuacán didn’t disappear overnight. It slowly became a monument instead of a metropolis.

The collapse changed everything:

- No single city dominated central Mexico anymore

- Power shifted to regional centers like Tula and beyond

- Trade networks replaced imperial control

Music & Instruments

What daily life sounded like, rhythm, breath, and vibration.

Instruments You Would Have Heard

Most instruments were percussion and wind-based, made from clay, wood, bone, shell, reed.

- Drums (Huehuetl & Teponaztli):

- Hollowed wood or slit drums

- Deep, resonant, heartbeat-like

- Played in ceremonies, processions, and public gatherings

- Flutes:

- Made of clay, bone, or reed

- Breath-heavy, sometimes piercing, sometimes soft

- Used for ritual, storytelling, and accompaniment

- Ocarinas & whistles:

- Often animal- or human-shaped

- Used in ritual, play, and ceremony

- Rattles:

- Seeds, gourds, shells

- Worn on the body or shaken by hand

- Conch shell trumpets:

- Loud and ceremonial

- Used to call attention or mark sacred moments

A Modern Playlist

No one pressed record in 900 AD. What we have instead are modern musicians using ancient instruments and techniques. These tracks give us a sense of the sounds, not a perfect copy of the past.

- “Teponaztli y Huehuetl” – Xavier Quijas Yxayotl

Deep drums and breathy flutes; very grounded and ceremonial. - “Música Prehispánica Mexicana” – Jorge Reyes

Ambient, ritual-focused recreations using traditional instruments. - “Concheros Ritual Music” – Traditional

Later continuity, but rhythmically useful for understanding communal dance sound. - “Mayan Ceremony Music” – Aj Tzuk

Modern Maya musicians using ancestral instruments and patterns. - “Ocarinas & Flutes of Ancient Mexico” – Smithsonian Folkways (various artists)

Clean recordings of instrument sounds without heavy modern layering.

Media You Can Watch or Read Today

Stories, films, and books that help you visualize the world you just stepped into.

Adults

Movies

- Apocalypto (2006)

Language: Yucatec Maya

Subtitled: English

Visceral, intense, and controversial, but visually immersive. This film drops you into a late Classic–Postclassic Maya world of jungle cities, ritual, fear, and survival. It’s not gentle, and it’s not perfect, but it feels like a world where ritual, violence, and daily life collide.

Books

- Popol Vuh (various translations)

Language: Originally K’iche’ Maya

Available in: Spanish & English translations

This is the Maya creation story. Gods, twins, underworld trials, cosmic balance. It’s not light reading, but it’s foundational. If you want to understand how people in this world thought about life, death, and duty, this is it. - Aztec – Gary Jennings

Language: English

Translated: Spanish editions available

A sweeping historical novel that follows one man through pre-Hispanic Mexico. It’s graphic, intense, and very adult, but meticulously researched and unmatched in its ability to make the world feel lived-in. - Gods of Jade and Shadow – Silvia Moreno-Garcia

Language: English

Translated: Spanish available

Not historical fiction in the strict sense, but deeply rooted in Maya cosmology and Mexican myth. Think folklore, gods walking among humans, and the long shadow of ancient belief bleeding into later eras.

Kids

Kids TV & Streaming Series

- Las Leyendas (Netflix)

Language: Spanish (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 8–12

This one’s spooky-but-fun. It pulls from Mexican folklore, Indigenous legends, and pre-Hispanic vibes without being scary in a nightmare way. Think monsters, mystery, jokes, and friendship, great if your kid likes mythology and a little edge. - Maya and the Three (Netflix)

Language: English (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: Spanish available

Ages: 7–12

It’s fantasy, not strict history, but it’s clearly inspired by Mesoamerican cultures. Bright colors, strong girl lead, gods, monsters, and a big adventure story. - Once Upon a Time… The Americas (Érase una vez… América)

Language: Spanish (original)

Dubbed: English versions exist

Ages: 7–11

Old-school educational animation, but solid. Episodes cover pre-Hispanic civilizations in a clear, kid-friendly way. Not flashy, but great if you want something calm, factual, and short.

Kids Movies

- The Road to El Dorado (2000)

Language: English (original)

Dubbed: Spanish available

Ages: 7–11

Not accurate in details, but useful for visual vibes: big cities, gold, temples, markets. It’s funny, musical, and light. - Nahuala: The Legend of the Nahuala (La Leyenda de la Nahuala)

Language: Spanish (original)

Dubbed/Subtitled: English available

Ages: 7–11

Part of the same universe as Las Leyendas. Slightly spooky, but playful and rooted in Mexican myth. Good intro to folklore without heavy themes.

Kids Books

- The Corn Grows Ripe – Dorothy Rhoads

Language: English

Translated: Spanish editions available

Ages: 9–12

A gentle chapter book about a Maya boy growing up and learning responsibility. No action-movie drama, just daily life, family, and growing up. Great if your kid likes thoughtful stories. - Aztec, Inca & Maya (DK Eyewitness Books)

Language: English

Translated: Spanish editions available

Ages: 7–12

If your kid loves flipping through pictures and facts, this is gold. Artifacts, clothing, food, homes, very skimmable and great for independent reading. - Popol Vuh for Children (various adaptations)

Language: Spanish & English versions available

Ages: 9–12

Simplified retellings of Maya creation stories. Best for kids who enjoy mythology and don’t mind gods, tricksters, and cosmic drama.

After walking through homes, markets, rituals, and family life, the question isn’t just could you survive — it’s what would feel hardest to let go of… and what might actually feel grounding?

Tell me what stood out to you, or tag me on social so we can keep the conversation going.

Leave a comment